Primordial Pathways of Aging: The Four Plant-Animal Genes That Shaped Eukaryotic Longevity-

Conserved Regulatory Genes from Horvath’s Universal Epigenetic Mammalian Aging Study: A Comparative Genomic Overview

Adapted from Horvath’s Universal Epigenetic Mammalian Aging Paper (Nature, August 2023)

Abstract

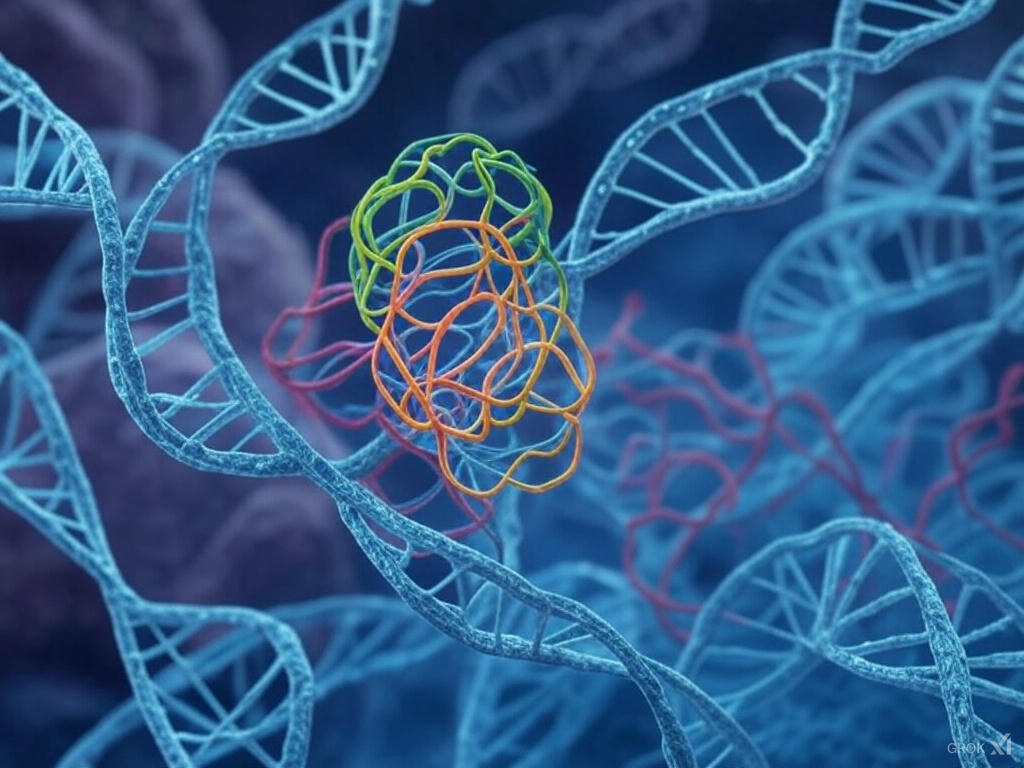

How deeply rooted are the molecular drivers of aging, and what does their conservation across plants and animals reveal about longevity itself? Building on Horvath’s landmark epigenetic clock findings (Nature, August 2023), this comparative genomic study probes 49 pivotal genes in mammals, fish, reptiles, birds, insects, plants, bacteria, and archaea. Strikingly, only four of these genes—LARP1, SNX1, HDAC2, and PRC2—emerge as universal eukaryotic anchors, linking epigenetic and developmental processes from leaves to limbs. Beyond these plant-present regulators, additional tiers of conservation appear in insects—yet vanish in simpler prokaryotes—revealing a layered evolutionary tapestry of increasing regulatory sophistication. This cross-kingdom perspective offers potent insights for aging researchers and evolutionary biologists alike, suggesting that the very architecture of longevity is inscribed into genes that first took shape at life’s eukaryotic dawn.

(Note these are the genes described in Horvath’s first draft of his seminal paper they changed somewhat over the next 2 revisions to include SP1 and some others . Due to its importance SP1 was added to this list of the original 48, but the last revision gene list will differ somewhat from this one.)

Introduction

In Horvath’s seminal work on universal epigenetic aging clocks, a set of 49 genes (48 original plus SP1) emerged as crucial regulators of development, metabolism, and chromatin organization in mammals. By comparing these genes across numerous phyla, Horvath and colleagues identified important patterns of evolutionary conservation, linking core transcriptional and epigenetic regulators to aging processes. This cross-kingdom perspective reveals which molecular components are ancient and ubiquitous (present in nearly all eukaryotes), and which arose more recently to underpin the specialized needs of animals—particularly vertebrates.

This article summarizes the major findings regarding the presence or absence of these 49 genes in key lineages. First, we describe the four genes that are conserved even in plants, underscoring their importance and ancient origin. Next, we highlight additional genes found in insects, marking the second tier of widespread regulatory modules. Finally, we note the many genes that remain vertebrate-specific, reflecting advanced developmental pathways. All data derive from the presence/absence table accompanying Horvath’s study.

1. The Four Genes Found in Plants: Cornerstones of Eukaryotic Regulation

Only four of the 49 genes—LARP1 (row 9), SNX1 (row 19), HDAC2 (row 40), and PRC2 (row 45)—show clear and consistent orthologs in nearly all plant species surveyed. Their broad conservation from plants to mammals underscores fundamental roles in RNA metabolism, protein trafficking, and chromatin regulation.

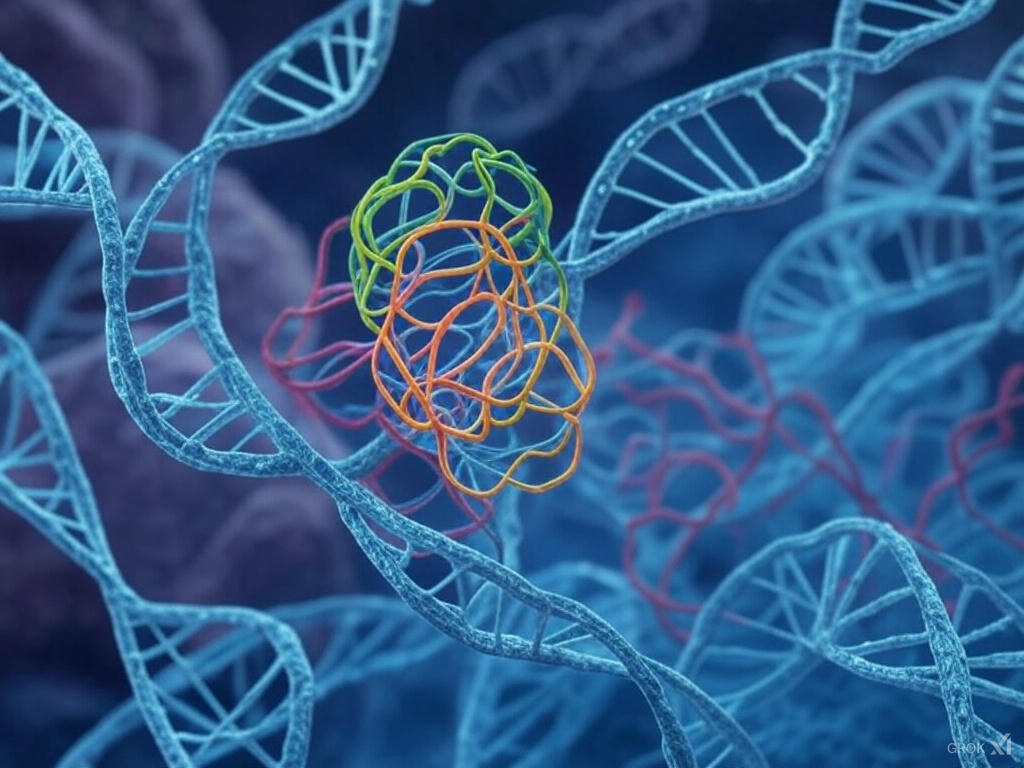

1.1 LARP1

- Function: La‐related protein 1 (LARP1) binds RNA, influencing mRNA stability and translation.

- Role in Aging/Epigenetics: By regulating RNA turnover, LARP1 influences cellular stress responses and protein synthesis. In Horvath’s aging context, it might modulate the translation of key longevity factors. (NOTE: It has been described on other blog posts that it might actually be short LARP1, an unstudied lncRNA homologue of the canonical long LARP1 protein that is actually the highly conserved aging gene-see the 4 Horseman of aging blog post ) .

1.2 SNX1

- Function: Sorting Nexin 1 (SNX1) is crucial for endosomal sorting and vesicular trafficking. It helps recycle membrane receptors or transport them to the lysosome for degradation.

- Role in Aging/Epigenetics: Proper proteostasis and receptor trafficking are vital for cellular homeostasis. Dysregulation of SNX1 pathways could contribute to age-related declines in membrane signaling fidelity.

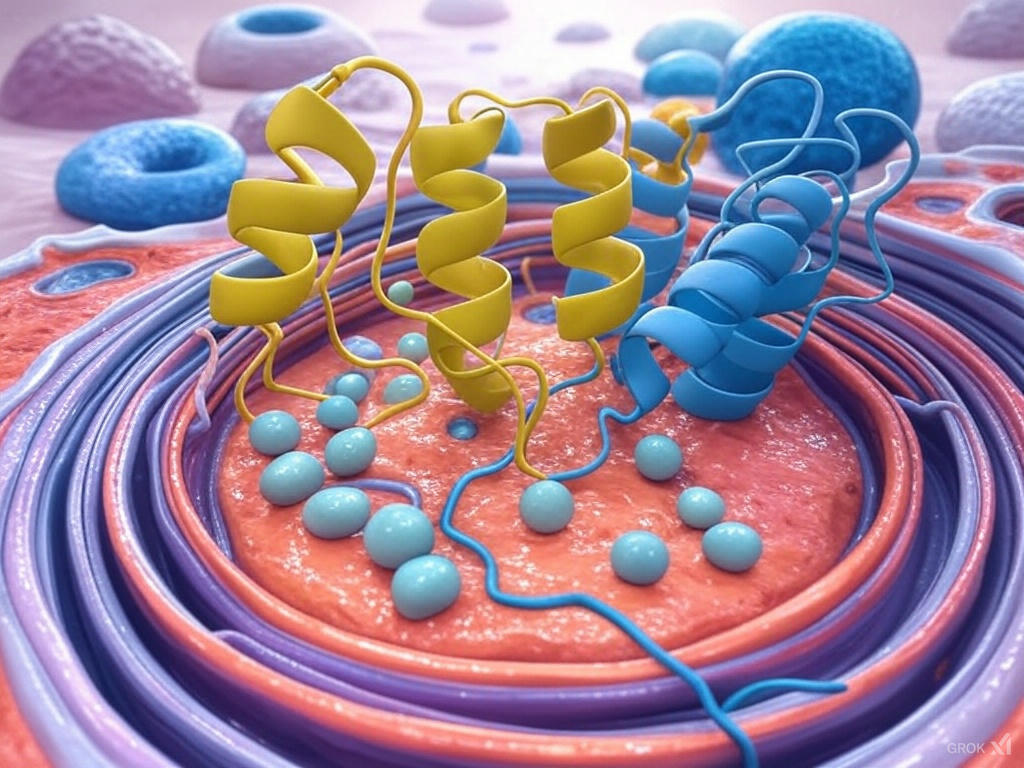

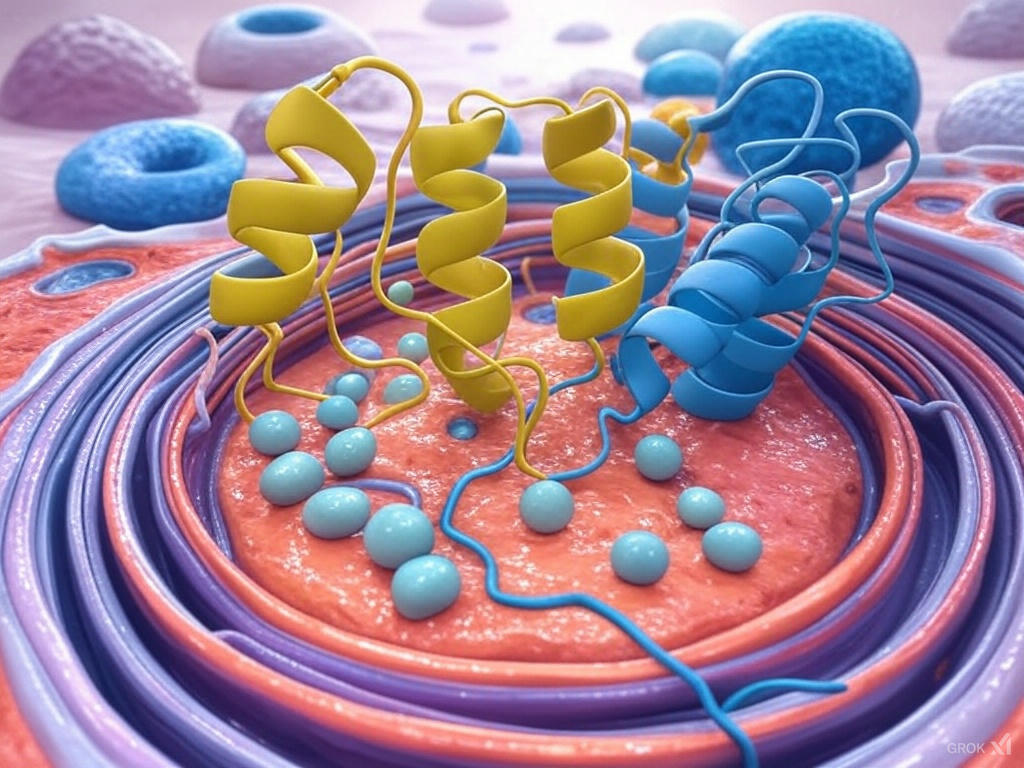

1.3 HDAC2

- Function: A histone deacetylase, HDAC2 removes acetyl groups from histones, impacting chromatin structure and gene expression.

- Role in Aging/Epigenetics: Histone deacetylases are major epigenetic modulators, altering gene expression profiles that shape aging trajectories. HDAC2’s regulation of chromatin accessibility is a central theme in Horvath’s epigenetic clock.

1.4 PRC2

- Function: The Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 is a multi-protein assembly that methylates histone H3 at lysine 27, establishing repressive chromatin marks.

- Role in Aging/Epigenetics: PRC2-driven chromatin silencing is central to development, stem cell identity, and cellular senescence. Horvath’s study emphasizes how PRC2 disruptions can accelerate or modulate aging through global transcriptional changes.

Taken together, LARP1, SNX1, HDAC2, and PRC2 represent the deep eukaryotic core of epigenetic and post-transcriptional regulation. Their presence across animals and plants—and sometimes in fungi—affirms their essential roles in genome management, cellular metabolism, and developmental control.

Taken together, LARP1, SNX1, HDAC2, and PRC2 represent the deep eukaryotic core of epigenetic and post-transcriptional regulation. Their presence across animals and plants—and sometimes in fungi—affirms their essential roles in genome management, cellular metabolism, and developmental control.

2. Additional Genes Present in Insects: Expanding the Regulatory Toolkit

Beyond these four, many other genes appear in insects but not in plants. These primarily encode transcription factors (homeobox, forkhead/FOX, T-box families) and certain nuclear receptors or signaling proteins. Although insects do not share some vertebrate-specific expansions (e.g., certain neural factors or antisense RNAs), they retain a conserved “toolkit” crucial for multicellular patterning, neural development (in simpler forms), and metabolic regulation.

Below are selected genes that highlight crucial functions in insects and vertebrates (but not plants). Each is implicated in Horvath’s mammalian aging model and has a recognized homolog in insect model organisms like Drosophila:

2.1 c‐JUN (row 48)

- Function: A proto-oncogene and AP-1 transcription factor subunit.

- Importance: Modulates stress responses, cell proliferation, and apoptosis. In insects (Drosophila Jun), it directs gene expression changes during development and stress adaptation.

2.2 FOXB1 (row 5) / FOXD3 (row 34)

- Function: Forkhead/FOX transcription factors regulating embryogenesis and tissue differentiation.

- Importance: FOX family members orchestrate axis formation in insects and vertebrates. Their roles in adult stem cell maintenance connect them to aging processes.

2.3 ZIC Genes (e.g., ZIC1, ZIC2, ZIC4, ZIC5; rows 7, 10, 28, 29)

- Function: Zinc-finger transcription factors essential in early neural patterning.

- Importance: In insects (odd‐paired gene), they drive segmental patterning and neuron specification, linking to broad morphological and developmental control.

2.4 NKX2 (row 44)

- Function: NK2 homeobox transcription factors (e.g., tinman in insects, NKX2-5 in vertebrates) shape heart and midline development.

- Importance: In Horvath’s model, NKX2 genes are part of the embryonic blueprint and can be reactivated or repressed during aging or tissue regeneration.

2.5 POU Domain Genes (e.g., POU3F2, row 18)

- Function: POU family transcription factors, crucial for neural fate specification.

- Importance: In insects, drifter/pdm-1 are functionally analogous. The mammalian POU domain expansions factor into neurogenesis and cortical development—processes intricately tied to aging phenotypes.

2.6 T‐box Genes (e.g., TBX18, row 23)

- Function: T-box proteins that control broad developmental decisions, from mesoderm induction to limb patterning.

- Importance: In Drosophila, T-box equivalents appear in key embryonic specification steps; in mammals, T‐box genes remain crucial in organogenesis and aging tissue repair.

2.7 Nuclear Receptors (e.g., NR2E1, row 20)

- Function: Transcription factors responsive to hormonal or metabolic signals, shaping gene expression in neural and developmental contexts.

- Importance: In insects, smaller sets of nuclear receptors handle molting and metamorphosis. Mammalian expansions link to metabolism, circadian regulation, and longevity.

Across insects, these genes coordinate fundamental patterning and physiological processes. Horvath’s universal aging clock highlights their capacity to integrate environmental cues with epigenetic states. Although insects lack the full mammalian repertoire (especially neural complexity and certain antisense RNAs), the shared scaffolds lay the evolutionary groundwork for more specialized vertebrate functions.

3. Additional Vertebrate-Specific Genes: Refining Complexity

Finally, an array of genes in Horvath’s list are present in mammals, fish, reptiles, and birds but have no insect homolog (or only extremely distant domain similarity). Examples include NANOG (pluripotency factor), BDNF (neurotrophic factor), NRN1 (neuritin), and multiple antisense RNAs like DLX6‐AS1, OBI1‐AS1, which appear restricted to mammals or a narrower subset of vertebrates. These expansions reflect the increasing complexity of vertebrate neural systems, immune responses, and advanced tissue organization.

Notable vertebrate‐only examples:

- NANOG (row 46): Central to embryonic stem cell self‐renewal in mammals. Absent in insects and plants, underscoring its specialized role in vertebrate pluripotency.

- BDNF (row 47): A key growth factor for neurons. In insects, simpler neuronal growth signals exist, but the advanced vertebrate nervous system requires robust neurotrophic factors like BDNF.

- DLX6‐AS1 (row 11) and OBI1‐AS1 (row 35): Long noncoding RNAs that modulate expression of protein-coding neighbors in mammalian contexts. Such antisense transcripts often exhibit lineage-specific evolutionary patterns.

4. Absent in Bacteria and Archaea

A major takeaway is that no genes from this set have orthologs in prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea). This underscores how eukaryote-specific organizational features—compartmentalized nuclei, histone-based chromatin, and complex transcription/splicing factors—have no direct analogs in prokaryotic lineages.

Conclusion

Horvath’s Universal Epigenetic Mammalian Aging paper (Nature, August 2023) reveals a powerful map of evolutionarily conserved regulators. Four core genes—LARP1, SNX1, HDAC2, and PRC2—are found across plants, insects, and vertebrates, underscoring their primacy in eukaryotic biology. A broad insect set of homeobox, forkhead, T‐box, POU, nuclear receptor, and polycomb genes forms the second tier of regulatory importance, crucial for multicellular development and epigenetic states. Finally, vertebrate‐only (or primarily vertebrate) genes enrich neural, immune, and tissue complexity, aligning with advanced aging pathways.

This hierarchical layering of regulatory complexity offers a macroevolutionary perspective on how epigenetic and transcriptional frameworks have diversified. In aging research, understanding which factors are truly universal versus lineage‐specific can inform both fundamental geroscience and the quest for translational interventions. As Horvath’s study demonstrates, mapping these genes across life’s domains provides profound insight into why certain epigenetic clocks behave consistently—and how the universal architecture of regulation underlies aging in every organism that shares this genetic toolkit.

Taken together, LARP1, SNX1, HDAC2, and PRC2 represent the deep eukaryotic core of epigenetic and post-transcriptional regulation. Their presence across animals and plants—and sometimes in fungi—affirms their essential roles in genome management, cellular metabolism, and developmental control.

Taken together, LARP1, SNX1, HDAC2, and PRC2 represent the deep eukaryotic core of epigenetic and post-transcriptional regulation. Their presence across animals and plants—and sometimes in fungi—affirms their essential roles in genome management, cellular metabolism, and developmental control.