Ancient Blueprints of Decline:

How Four Evolutionary Waves Over 800 Million Years Shaped

the Aging We Know Today

Jeff T. Bowles – 2/7/2025

JeffTbowles.com

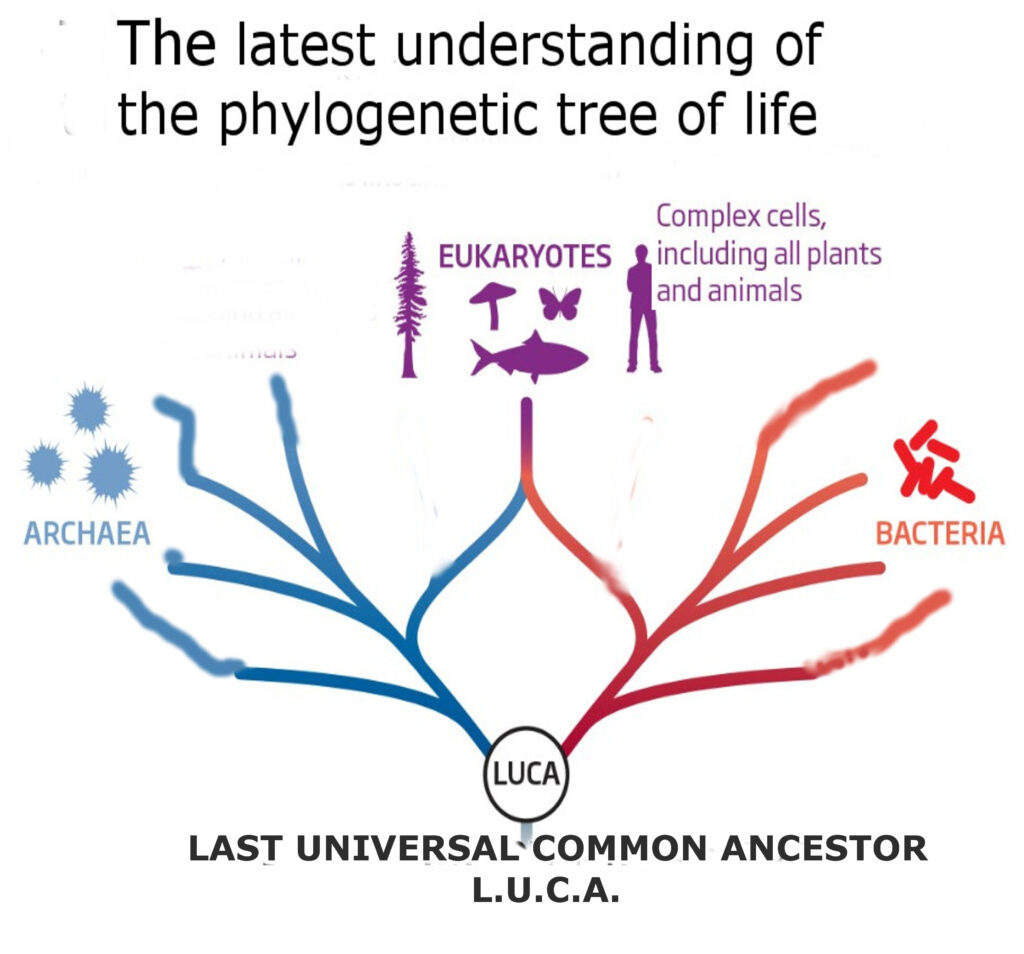

Introduction: Two Domains, One Mystery

Traditionally, we’ve taught that life is divided among multiple kingdoms (plants, animals, fungi, protists, etc.). Yet the most up-to-date phylogenetic analyses paint a simpler picture: essentially two great domains, bacteria and archaea—both single-celled, both asexual, overwhelmingly non-predatory (bacteria-well below 1%, archaea 0%), and both largely immortal as far as natural aging is concerned. Scientists have discovered living ancient bacteria in salt deposits, dormant for 250 million+ years. When revived, they replicate as if no time had passed. Archaea are well documented to live for 40,000 years and it is thought by some that they found living archaea that are also 250 million years old. Some researchers believe they have found living bacteria and archaea in salt deposits 830 million years old!

Why haven’t they become multicellular in all that time? Despite billions of years to evolve, most archaea and bacteria remain single-celled. There are no known “true” multicellular archaea. And although there are rare cases of groups of individual bacteria temporarily coming together to form fruiting bodies for reproduction they then dissociate back into single cell individuals again. One leading hypothesis is that strong selection pressures for stable asexual reproduction outweighed the benefits of complex multicellularity. But the real key event in the origin of complex life happened 2.5 billion years ago, when an archaeon engulfed a bacterium and truly became its brother’s keeper. This single act—endosymbiosis—led to single cell life forms with nuclei and mitochondria and catalyzed the rise of eukaryotes. From there, multicellularity, predation, sexual reproduction, and aging all took root, creating the biodiversity we see today.

Interestingly, this origin of eukaryotes formed from the union of two immortal life forms (bacteria and archaea) explains the puzzling fact that both embryonic stem cells and cancer cells which lack most differentiation (or genetic controls) can become immortal and able to divide forever. If eukaryotes had not evolved from immortal life forms, this would be considered quite a miracle indeed. This also suggests that cancer may simply be caused by cells reverting to their original ancestral state just as the first cell that will divide into a multicellular animal (ESC) is also mostly in its original ancestral immortal state. Interestingly, ESC’s, cancer cells, and as we will see, cells from progeria patients create energy via fermentation and do not use oxygen for energy production even when oxygen is present.

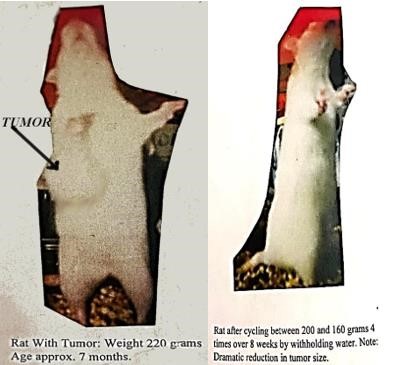

Another intersting idea coming from this analysis is that of the 3.8 billion years of evolution of life on earth, most of it occurred in single cell organisms that lived in water of the oceans. There have been land animals for maybe only 10% of this period of evolution or 400 million years. It is expected that cells from land animals have developed highly sophisticated defenses to surviving drought, while the cells of the original ancestral organisms likely have not. If this is true, it suggests that cancer cells, having lost the genetic controls of their land animal hosts, likely have lost their defense to dehydration. This then implies that an excellent treatment for cancer would likely be to restrict any liquids for a long period of time (say up to 8 days or more in humans) to cull the dehydration-vulnerable cancer cells while sparing the healthy dehydration-protected normal cells. This might explain my experimental results of having a rat’s 1/2- golf-ball-sized tumor basically self destruct and implode in about 4 days when her water was taken away which is detailed in my book Methuselah Rats etc… That tumor stayed in remission and remained the size of about a penny under her skin for 6 months or the equivalent of 20 years in human terms. (see picture at end of article).

Below, we’ll explore how aging might have four evolutionary “layers,” each traceable to a major leap in complexity.

Stage One (Aging System #1)

From Fermenting, Slow-Moving “Plant-Like” Ancestors (Approx. 800 million years ago)

Plant-Like, Fermenting Proto-Animal

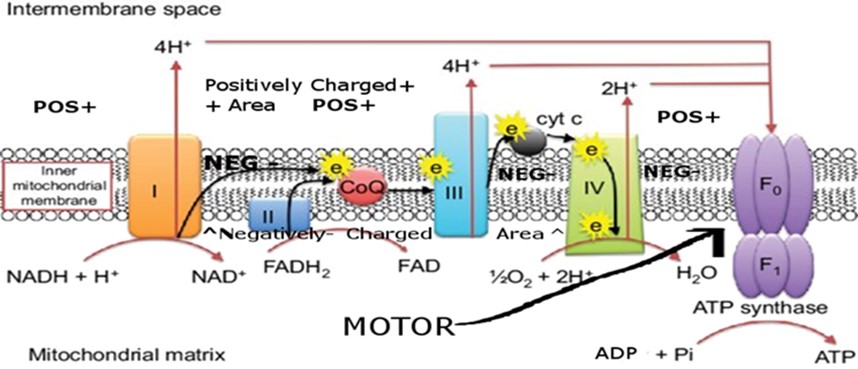

Early eukaryotes likely produced 2 ATP per glucose via fermentation, comparable to yeast or simple plants. They were slow and weakly mobile, with cilia or flagella that rotated gently to enable drifting or minimal crawling.

- Possible Cilia–ATP Synthase Link

- An intriguing speculation holds that the rotary mechanism of cilia inspired the rotor in ATP synthase, the enzyme that efficiently makes ATP in mitochondria and can spin at the rate of 7,000 RPMs 24/7.

- It’s possible that Complex IV of the electron transport chain which is responsible for 2 of the 10 protons produced by the electron transport chain, emerged first to power these early cilia movements, with other complexes (I–III) evolving in stages later to maximize ATP output. The number 2 appears here, and in the number of ATPs produced per molecule of glucose during energy produced by fermentation. Interestingly while the later evolved electron transport chain complexes 1 and 2/3 (1 and II/III) require the complicated molecules NAD+ and FAD as cofactors to produce protons, the presumably more ancient complex 4 (IV) requires only water as a cofactor.

- Earliest “Aging” Pattern

These primordial proto-animals likely had a structural-decline system reminiscent of how lamin A (a nuclear envelope scaffold protein) can fail and lead to cellular defects. Over time, sabotaging nuclear or internal structural integrity may have formed an early aging module—System #1. - Modern Echo: Progeria and Fermentation

- Progeria fibroblasts shift toward glycolysis/fermentation, mimicking these ancient cells’ low-ATP, plant-like metabolism.

- Progeria also presents truncated lamin A (progerin), mirroring a structural meltdown possibly rooted in developmental processes but reactivated in pathological aging.

- Yamanaka Factor KLF4 may help reverse these structural breakdowns, reinforcing its tie to epithelial/vascular integrity—i.e., System #1 vulnerabilities.

Stage Two (Aging System #2)

The Mitochondrial Revolution & Rapid Movement (Approx. 600 million years ago)

- Endosymbiosis: 36 ATP Instead of 2

- A seismic shift occurred when an archaeon engulfed a bacterium and that became the mitochondria, jumping from 2 ATPs (fermentation) to about 36 ATPs produced per molecule of glucose consumed.

- This unleashed energetic abundance, which propelled organisms toward greater speed, predation, and eventually more intricate body plans. This leg of evolution was allowed also by the Neoproterozoic event 800-500 million years ago when oxygen levels increased dramatically.

- Enhanced Mobility

- With more ATP available, organisms developed muscles, nerves, and even rudimentary ears and eyes to hunt, flee, or navigate more effectively.

- A Second Aging Layer Emerges

- High oxygen use by mitochondria leads to reactive oxygen species (ROS), byproducts that can damage proteins, lipids, and DNA.

- Over evolutionary time, manipulating mitochondrial function or ROS production provided a lever for aging: degrade mitochondria in older individuals, and high-energy tissues (brain, muscle, nerves) fall apart.

- Modern Echo

- Mitochondrial decline contributes to muscle wasting, neurodegeneration, and fatigue in older adults.

- The Yamanaka factor Sox2 is associated with neural and muscle regeneration, reflecting a possible renewal mechanism for these mitochondria-intensive tissues.

Stage Three (Aging System #3)

Advanced DNA Repair, Immune Function, Cancer & Apoptosis (Approx. 550 million years ago)

- Rise of Apoptosis & Complex Repair

- Multicellular life developed sophisticated DNA-repair genes (e.g., ATM, XP, CS) and programmed cell death (apoptosis) to control damaged or infected cells.

- Paradoxically, sabotaging these high-level repair and immune pathways—particularly in older organisms—lets aging accelerate via systematic cell loss or dysfunction or cancer.

- Third Aging Layer

- Defects in ATM (ataxia-telangiectasia) or XP/CS (xeroderma pigmentosum/cockayne syndrome) produce progeroid syndromes marked by heightened mutation rates, oxidative stress, cancer and neurodegeneration.

- These same proteins/pathways can exacerbate or trigger collapses in mitochondrial and vascular systems due to their colocalizing within mitochondria to suppress ROS production when functional, and also colocalizing with the spliceosome that produces the mRNA for lamin A, (Systems #1 & #2).

- Modern Echo

- Ataxia-telangiectasia features immune deficiencies, cancer susceptibility, and neurological decline—fast-forward versions of normal aging.

- Yamanaka factor c-Myc is intimately linked to cell growth and the balance between senescence and tumorigenesis—reflecting the DNA-repair dimension of aging.

Stage Four (Aging System #4)

Sexual Reproduction (Male/Female) & the “Master Switch” (Approx. 500 million years ago)

- Sex Evolves

- The emergence of meiosis and recombination and sex types supercharged evolutionary adaptability.

- With predation intensifying, sexual reproduction enabled rapid gene recombination and turnover, letting species adapt to predators and environmental shifts.

- The Werner’s syndrome protein (WRN) evolved as a helicase/exonuclease critical for genome stability in sexually reproducing organisms.

- Later sabotage of WRN (e.g., possibly via short LARP1–mediated mis-splicing) can unify earlier aging systems and drive a coordinated collapse.WRN Protein: A Late-Arriving Coordinator.

- The WRN protein does not appear in many somatic tissues until it is activated by a rise in sex hormones during puberty.

- Potential Implications for Meiosis

Although not directly stated in the literature , WRN’s functions could potentially impact meiosis:

DNA repair: WRN’s role in repairing double-strand breaks and resolving complex DNA structures might be relevant during meiotic recombination.

Telomere maintenance: WRN is involved in telomere metabolism, which is crucial for chromosome stability during cell division, including meiosis.

Recombination intermediates: WRN shows a preference for acting on strand invasion intermediates, which are also formed during meiotic recombination.

- Fourth Aging Layer

- Werner’s syndrome replicates nearly every hallmark of aging—cataracts, atherosclerosis, hair graying, cancer risk, etc. —but on a rapid timeline.

- The Yamanaka factor Oct4 interacts with WRN to possibly align reproductive signals with a final “master aging” circuit.

- Evolutionary Logic

- After an organism’s reproductive phase, from a population-genetics standpoint, continued survival matters less.

- By coordinating a broad meltdown across aging modules, System #4 ensures that once organisms have passed on genes, they gradually phase out and do not excessively contribute to the gene pool in a diversity-damaging manner.

Why This Matters

- Four Ancient Layers of Aging

- System #1: Rudimentary structural breakdown (like lamin A in progeria).

- System #2: Mitochondrial ROS damage, especially in high-ATP tissues.

- System #3: DNA repair/apoptosis sabotage (seen in ataxia-telangiectasia, XP, CS).

- System #4: Sexual reproduction & WRN “master aging” (Werner’s syndrome).

- Progeria’s Fermentative Shift

-

- Progeria offers a glimpse into how these systems can regress to an ancient mode. Cells rely more on glycolysis and express truncated lamin A—almost as though stepping back into Stage One of aging.

- Evolutionary “Program” vs. Accident

-

- Each system builds upon pre-existing vulnerabilities. Aging appears to be a layered synergy rather than mere wear-and-tear, fine-tuned by evolutionary pressures where older adults eventually decline or die off with evolution’s intent of limiting their genetic contribution to the gene pool.

- Sexual reproduction cements this by reshuffling genes, preventing predator-driven local extinctions of uniform populations.

- Therapeutic Implications

-

- Understanding which “layer” a therapy targets helps explain why some treatments slow only certain aspects of aging.

- Partial reprogramming (Yamanaka factors) can reverse different aging modules:

- KLF4 ↔ structural decline (System #1)

- Sox2 ↔ neuronal/muscle systems (System #2)

- c-Myc ↔ DNA repair/cancer interplay (System #3)

- Oct4 ↔ sexual/WRN-driven aging (System #4)

Conclusion

The evolutionary jump from immortal single-celled archaea and bacteria to complex multicellular eukaryotes brought about two new phenomena: aging and sex. We can trace this layered aging program across four major shifts:

- “Plant-like” structural decline grounded in early fermenting ancestors.

- Mitochondrial vulnerabilities from high-energy respiration.

- DNA repair and apoptosis complexities in multicellular organisms.

- Sex-driven “master aging,” coordinated by WRN and tied to post-reproductive lifespan.

From slow-fermenting proto-animals to mitochondria-fueled movements, from powerful immune/DNA repair pathways to the tight coupling of sex and lifespan, each evolutionary leap introduced a novel handle for aging. Cases like progeria highlight how easily cells can revert to an ancestral metabolic state, underscoring how deeply embedded these ancient programs are.

Ultimately, by decoding these four layers, we may discover how to decelerate, halt, or even reverse aging—tapping into the same ancient biological machinery that archaea and bacteria left behind billions of years ago when they chose the path of complex multicellularity.

© 2025 Jeff T. Bowles • JeffTbowles.com

This is a standalone blog post that could also be considered a de facto continuation of the blog post>>: https://jefftbowles.com/4-evolved-aging-human-systems/

If you haven’t read it, check it out!