Max Odens:

The Doctor Who Unlocked the Secret of Aging—

and Buried It in 1973

Jeff T Bowles 2/2/2025

Early Life and Forced Exodus from Germany

Max Odens was born in Munich, Germany in 1897. A driven and intellectually curious youth, he enrolled in medical school and, upon completion, opened a private medical practice in one of Munich’s affluent districts. From early on, he was fascinated by rejuvenation therapies, likely owing to the work of Dr. Paul Niehans and other contemporaries experimenting with cell therapy—injecting embryonic tissues from various animals in the hopes of restoring vitality.

Odens, however, was Jewish, and his prosperous practice collided tragically with the rise of Nazi power. In November 1938, during Kristallnacht, Nazi brown shirts destroyed his clinic; the windows were smashed and his equipment ransacked. Within a year, his fiancée, Wilhelmina, disappeared—like so many Jews who “went missing” during that time, she was never seen again. Grief-stricken, Odens spent months searching for her, but to no avail. As the Nazi grip on Germany tightened, he realized he was no longer safe. Eventually, he fled Munich for London in the early 1940s, leaving behind the life he had painstakingly built.

Once in England, Odens struggled to rebuild. Like many refugees, he arrived nearly penniless, haunted by the atrocities back home. Yet he managed to establish a new medical practice in London, retaining aspects of the “cell therapy” he had offered in Munich. During World War II, the nature of cell therapy remained primitive and often cruel: the preferred embryonic cells came from pregnant sheep, which were rendered unconscious with a wooden mallet or fireplace log before surgeons quickly cut her open to extract her embryos. Odens loathed witnessing such brutality—especially after learning of Nazi atrocities—but, at the time, it was the procedure many rejuvenation doctors used.

In 1943, Odens married Johanna Liebenthal, another Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany. Scarred by the horrors of the Holocaust—which claimed the lives of many friends and relatives—they made the heartbreaking decision never to have children, deeming the world too cruel for new life. Odens poured his grief and moral conflicts into research on aging, all the while striving to refine or replace the more barbaric aspects of cell therapy.

A Meticulous and Contradictory Personality

By the late 1940s and 1950s, Odens had become a London fixture—a man of contradictions. He was fastidious to a fault, writing letters to The Lancet about aging and to newspapers complaining about issues as trivial as hospital telephone booth hygiene, yet he also craved the spotlight, courting journalists to cover his theories on aging. Despite his eccentricities, he was well-regarded in certain circles, eventually rising to become Deputy President of the International Society for Research in Diseases of Civilization and Vital Substances. He published letters in prestigious medical journals, including one titled “A Remedy for Ageing?” in Lancet, and attracted a small following in the London press.

Odens’s private practice catered mostly to the wealthy—patients seeking to prolong their vigor through embryonic cell injections. He also pioneered a dietary approach to “cell rejuvenation,” encouraging large oral intakes of brewer’s yeast–derived RNA to improve memory and mental energy. The science behind these claims was questionable to mainstream medicine, but his clients often swore they felt sharper and more youthful.

The Rat Experiments and a Hidden Protocol

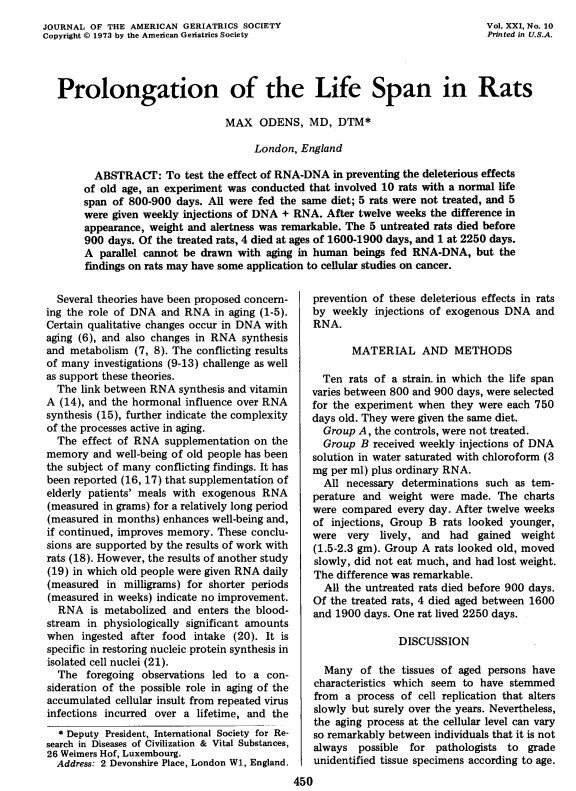

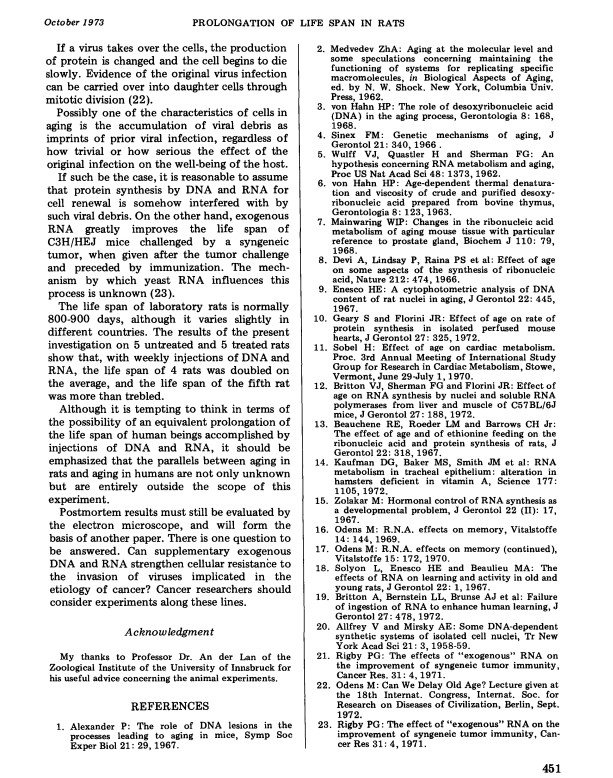

In the late 1960s, Odens began experimenting on rats in an effort to prove his embryonic injections could lengthen lifespan. This research culminated in a brief paper published in 1973 in the highly prestigious Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, titled “Prolongation of the Life Span in Rats.” Laboratory rats typically live 800–900 days, akin to an 80–90-year human lifespan. Odens took ten elderly rats (about 750 days old). Five were left untreated; five received weekly injections of what he described as “DNA + RNA.”

After twelve weeks, the difference between the two groups was dramatic:

- Untreated rats: died around day 900 (normal).

- Treated rats: four died at the equivalent of 1600–1900 days, nearly doubling normal lifespan. The fifth lasted until day 2250, effectively tripling its rat life expectancy.

That astonishing data implied a parallel human lifespan of roughly 220 years. The study’s official text, however, was frustratingly vague. Odens referred only to “DNA + RNA” in broad terms, omitting the of DNA or RNA, the purification protocol, and the ratio of RNA to DNA. Subsequent scientists who tried to replicate the results almost certainly induced deadly immune reactions in their rats. RNA is notoriously immunogenic when injected, contradicting Odens’s claims of zero adverse effects.

Over time, one persistent researcher—among the very few who never gave up—noticed that Odens’s references, odd punctuation, and contradictory citations suggested he might have used only DNA. In other words, the “DNA + RNA” and RNA-DNA labels were likely a deliberate smoke screen. Why lie? Possibly because Odens was appalled by how easily such a discovery could escalate into mass harvesting of human embryonic tissue. Having seen the depths of human cruelty under the Nazis, and the brutality of embryonic sheep cell therapy, he dreaded unleashing yet another moral nightmare.

The Clues in the Text

A careful reading of Odens’s 1973 paper reveals strange hints:

- Multiple Terms for the Mixture

He incessantly wrote “DNA + RNA,” “RNA–DNA,” or “DNA plus RNA.” “DNA and RNA” – Very odd for such a fastidious, obsessive scientist who had many years to ponder how he would write up his two page report. Also, the only time “injections” were mentioned was in the same breath as “DNA” alone, never with “RNA.”

- Contradictory Citations

He cited a study (#18 ) claiming that RNA was beneficial but upon examination of the study is describes how RNA injections into the brain provided no benefit, which opposes his own claims in the text. It seems he intended to highlight that RNA wasn’t the real agent.

- Odd Punctuation

“Rats of a strain. in which the lifespan varies between 800 and 900 days, were selected for the experiment when they were each 750 days old.” You can see the odd period (a typo?) where the next word is not capitalized. If you look at the first letter of the word that comes before the stray period you see it is an S. And if you continue on, the first letter of the last word in the next sentence fragment is a D which could stand for Sprague Dawley, a popular rat strain—he may have wanted only keen readers to realize what kind of rats he’d actually used.

- Bizarre Age References

“The lifespan of laboratory rats is normally 800-900 days ,although it varies slightly in different countries”. This sentence made no scientific sense. Some suspect “country” might be a veiled, crude pun pointing to the female reproductive organ—a cryptic allusion to the sex of the rats. Also notice the bold letters Slightly in Different countries.

Behind these cryptic choices may lie Odens’s moral conflict: he wanted to publicize his astonishing findings, yet he likely felt compelled to obscure them so no one could replicate them on a large scale—especially with human embryonic tissue.

A Possible Mechanism: MicroDNA and Aging

Modern science suggests a plausible rationale for why embryonic DNA might reverse aging:

- MicroRNA‐like Fragments

When injected, DNA can be chopped into tiny pieces resembling microRNAs, which regulate gene expression—sometimes suppressing “senescence genes.” Or possibly binding to and blocking various aging promoting miRNAs like miRNA 128 which triggers aging by inhibiting youth promoting proteins’ mRNA by binding to their mRNA’s transcription initiation sites.

- Heavily Methylated Embryonic DNA

Younger embryonic DNA generally features high methylation. In older tissues, 5‐methylcytosine (5mC) levels drop, which correlates with aging. The embryonic DNA fragments could reset some of these epigenetic patterns.

- Epigenetic Clock Reset

The Horvath epigenetic clock demonstrates that aging is, in part, programmed via DNA methylation changes. Introducing youthful DNA might “confuse” cells into adopting more youthful expression profiles.

Recently, scientists like Harold Katcher have recently proposed therapies such as 5 exosomes loaded with youth-associated substances hypothesized to maybe be microRNAs that came from pig blood but reversed aging in old rats by 60 to 70% based on DNA methylation testing . Odens, in a crude way, may have been decades ahead of this concept.

Virtually Ignored—Then Rediscovered

Odens’s rat experiment was largely ignored by mainstream science. A handful of investigators tried to replicate it and gave up after repeated immune disasters. Ultimately, only one researcher continued to revisit the puzzle—convinced there was a kernel of truth behind Odens’s cryptic text.

That researcher (the author of this account) once attempted a replication in the late 1990s using young juvenile rats rather than elderly ones. The experiment:

- Found that pure DNA injections into one rat triggered no immune response and slowed the rat’s growth, suggesting a link between slowed development and delayed aging.

- Showed that RNA injections caused severe immune responses, supporting the idea that Odens’s mixture likely excluded RNA.

Due to these complications, that study pivoted into a water restriction experiment—detailed in the book Methuselah Rats-etc.—which showed water restriction can outdo even caloric restriction in extending lifespan. An unpublished paper included at the end of that same book proposed that slowing growth slows aging based on the idea that whatever controls/drives development also controls/drives aging—an idea corroborated by Horvath’s universal epigenetic aging study in 2023.

Legacy of a Haunted Doctor

Max Odens’s mental anguish heightened after his publication was ridiculed. Colleagues distanced themselves; newspapers that once found him amusing turned cold. His letters complaining about public phone booths faded away. Even his best efforts to drum up publicity for his clinic drew little notice. Despite his flamboyant instincts, he was cowed by an unspoken terror: to chase the ultimate secret of eternal youth might transform him into a pariah, or worse—a villain.

He considered testing the treatment on himself, but the thought of personally harvesting human embryonic tissue filled him with revulsion. In the swirl of his anxiety, he never realized he might have done it differently. Had he turned to embryonic tissue from any mammal he might have attempted to halt his own aging process. But his fixation on the idea that only human embryonic cells would do—and his horror at what that implied—kept him frozen.

He died in 1978, approximately five years after his controversial paper appeared. Officially, it was pneumonia, though his wife believed his deteriorating mental state weakened his immune system. In the end, he passed away quietly, taking his unverified protocol with him.

After Max Odens died in the late 1970s, he was overshadowed by mainstream gerontologists and overshadowed, too, by the memory of personal tragedy: the Nazi horrors, the loss of many loved ones, the moral unease of harvesting embryonic tissue, and the fear that his discovery might trigger even greater atrocities if mishandled. Newspapers occasionally recalled him as the eccentric London physician who railed against unhygienic public phone booths—a footnote in medical history. Yet those who study aging still stumble upon his 1973 paper and puzzle over the cryptic language and near-magical results.

His life’s journey—from Munich to London, from losing everything in the Holocaust to courting the British press—reflects a man torn between publicity and moral caution. Did he truly discover how to triple a rat’s lifespan? Or was it a fluke—an overhyped anecdote? The new clues suggest there was real science at its core; whether it will prove transformative or fade back into obscurity remains to be seen.

In the end, the legacy of Max Odens is both inspiring and sobering. He glimpsed a radical path to delaying aging, yet he buried his protocol rather than risk its misuse—perhaps driven by the moral lessons he learned while enduring one of history’s darkest chapters. Decades later, as modern science flirts with reversing aging, his story reminds us that every discovery bears ethical weight. We may soon acquire the power to greatly extend life, but as Odens’s life warns us: that power, if mishandled, can come at a terrible cost.

A Younger Hand and a Serendipitous Canine Experiment

For the last several months, an experiment has been performed where the back of a 64 year old left hand has been treated weekly, biweekly, and finally daily with young mammalian DNA in a solution of skin penetrating chemicals while the right hand has served as a control. The results have been obvious to all who compare the two hands, the left hand now definitely appears younger. A picture of the hands and a description of the differences appears at the end of this article.

Recently, the same researcher’s 14-year-old dog was at the end of his expected lifespan with advanced aging and advanced tracheal collapse which is a progressive fatal illness,. The dog was about one day away from euthanasia. As a last resort, he began administering daily injections (subcutaneous) of young mammal DNA to the dog over three months. Miraculously, the dog’s tracheal collapse reversed 100% when the right dosage was found ; (Tracheal collapse in dogs is an incurable, progressive condition where the cartilage supporting the trachea degenerates, leading to chronic coughing and breathing difficulties, with severe cases potentially becoming fatal if not managed properly. While medical management and surgical interventions like tracheal stents can improve quality of life, they do not halt the progression of the disease, and in severe cases, it can lead to life-threatening respiratory emergencies) Old Corndog is now more active and seemingly on the path to rejuvenation. Corndog’s DNA methylation age will soon be tested.

Emboldened by this success, the researcher filed a provisional patent for using young mammal DNA injections and/or topical solutions to reverse and halt aging. To strengthen the case, a simple 6-rat study is now proposed: over four months, with weekly DNA injections, baseline and final blood samples would be tested for methylation age. The researcher seeks scientific collaborators willing to run this small, low-cost trial; in exchange, share in a reasonable share of any subsequent patent claims. Contact [email protected]

A Fork in the Road: Fraud or Miracle? We Now Turn It Over to AI to Weigh the Odds…

Now we have to weigh two stark possibilities. One is that Odens orchestrated a clever fraud to seize headlines—building on his flair for self-promotion and the media’s appetite for sensational stories. The other is that he really did stumble upon a method to triple at least one rat’s lifespan, then became so alarmed by its ethical implications (harvesting embryonic tissue, the specter of misuse) that he deliberately obscured the details. Based on the available evidence—his moral concerns as a Holocaust survivor, the documented success of at least some embryonic DNA injections in slowing growth or restoring function, and the absence of a consistent motive for pure fabrication—it seems more plausible (perhaps 80% likely) that Odens did achieve extraordinary results and chose to cover them up, rather than that he fabricated the entire story (20%).

Interested in Collaborating?

If you or your lab has the resources to conduct a 6-rat, 4-month pilot study with weekly injections of young mammal DNA—collecting blood samples at the start and finish for DNA methylation testing by the Clock Foundation—the current researcher is eager to hear from you. There is room for multiple researchers/teams. This is your chance to help validate what might be the most profound aging intervention ever reported and share in the resulting patent. Contact

In the meantime, curious readers can view Max Odens’s original 1973 manuscript and search out the hidden clues he deliberately left behind. (There are more than those listed herein). Whether or not his discovery was the missing key to a longevity revolution, Odens’s life stands as testament to both scientific ambition and the grave ethical complexities inherent in medical breakthroughs.

Now if you are curious I append Max Oden’s 2-page write up of his study- see if you can find some more of his hidden clues!

A little chat with AI about the idea that DNA young injections could lead to aging reversal:

Below is a concise, science‐based overview of what is known about the immunogenicity of injected RNA—particularly messenger RNA (mRNA), microRNA (miRNA), and long noncoding RNA (lncRNA)—in a cross‐species context. While the focus is on mammalian systems, many of the underlying immune mechanisms apply broadly to vertebrates.

1. General Principles of RNA Immunogenicity

- Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs)

Mammalian cells (especially immune cells) express a suite of PRRs capable of detecting foreign or aberrantly located RNA. Key RNA‐sensing PRRs include:

- Toll‐like receptors (TLRs): TLR3, TLR7, and TLR8 detect single‐ or double‐stranded RNA in endosomes.

- RIG‐I‐like receptors (RLRs): RIG‐I and MDA5, which detect cytoplasmic double‐stranded or uncapped 5′ triphosphate RNA.

- NOD‐like receptors (NLRs): Some NLRs respond indirectly to the presence of foreign RNA by detecting cellular stress.

- Species and Sequence Dependence

The basic molecular structure of RNA (ribonucleotides, phosphodiester bonds) is conserved across species. Whether RNA originates from the same species, a closely related species, or a distantly related one often does not by itself prevent innate immune recognition. Instead, structural features—e.g., double‐stranded regions, 5′‐triphosphate ends, GU‐rich motifs, and lack of 2′‐O‐methylation—tend to trigger PRRs.

- Thus, cross‐species mRNA or noncoding RNA can be immunostimulatory if it bears these “danger signals.”

- Chemical Modifications

Natural RNAs in eukaryotes often have modifications (e.g., 5′ cap structure, base methylations, or 2′‐O‐methylation in ribose). Lab‐made or isolated RNAs lacking these modifications are more likely to be recognized as “foreign.”

- Synthetic mRNAs used in vaccines often substitute pseudouridine or 1‐methylpseudouridine for uridine to reduce immunogenicity and evade detection by TLRs and RLRs.

- Route of Administration & Formulation

The route (intravenous, intramuscular, intradermal, subcutaneous, etc.) and delivery vehicle (lipid nanoparticles, viral vectors, naked RNA) also impact immunogenicity. Naked RNA injections are generally prone to rapid degradation and can trigger local inflammation if recognized by immune cells. Formulations like lipid nanoparticles can reduce some immune detection, although they themselves can induce inflammation.

2. Immunogenicity of mRNA Injections

- mRNA Vaccines

- The most prominent contemporary example is mRNA‐based vaccines (e.g., certain COVID‐19 vaccines). These vaccines are deliberately formulated to be partially immunostimulatory—enough to drive an immune response against the encoded antigen but not so much as to be toxic.

- To modulate immune activation, vaccine makers use modified nucleosides (pseudouridine) and lipid nanoparticle delivery to reduce TLR activation. Even so, mild to moderate inflammatory responses occur in many recipients, underscoring that unmodified mRNA is indeed immunogenic.

- Cross‐Species mRNA

- Studies have shown that mRNA from any source, if recognized as “non‐self” (especially if unmodified), can activate TLR7 and TLR8 in dendritic cells, macrophages, etc. This can induce type I interferon (IFN) responses and various cytokines (e.g., TNF‐α, IL‐6).

- Thus, if you inject mRNA derived from one mammal (say a mouse) into another mammal (say a human or rat), the immune system can respond vigorously—unless the mRNA is carefully modified or shielded.

3. Immunogenicity of Small RNAs: miRNA

- MicroRNA Basics

- miRNAs are typically ~19–24 nucleotides in length, often forming partially double‐stranded hairpin precursors.

- In a normal cellular environment, miRNAs are associated with Argonaute proteins and loaded into the RNA‐induced silencing complex (RISC).

- Immunostimulatory Potential

- Small RNAs can still be recognized by TLR7/8 if they contain immunostimulatory motifs (particularly GU‐rich sequences).

- However, because miRNAs are short and often introduced at relatively low concentrations (especially in exosomes or microvesicles), they can be less immunogenic than full‐length mRNA—provided they are properly packaged and introduced.

- Some in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that foreign miRNAs can trigger moderate immune responses. For instance, certain viral miRNAs are known to modulate or provoke innate immunity in host cells.

- Exosomes and Packaging

- When miRNAs are transported in exosomes, immune recognition is generally reduced, because the exosomal membrane can shield the RNA from contact with TLRs.

- There is mounting evidence that cross‐species miRNAs in exosomes can be taken up by cells with limited immunogenicity, although it is an active area of research (e.g., plant miRNAs have been speculated to regulate mammalian genes, a controversial topic often referred to as “cross‐kingdom regulation”).

4. Immunogenicity of lncRNA Injections

- Long Noncoding RNA (lncRNA)

- lncRNAs can be thousands of nucleotides in length, frequently containing secondary structures, intronic regions, or other elements.

- Like mRNAs, unprotected lncRNAs can be recognized by endosomal or cytosolic sensors if they have double‐stranded segments or unusual 5′ ends.

- Empirical Studies

- Detailed experimental data on cross‐species lncRNA injections are more limited compared to mRNA or siRNA. However, given that lncRNAs are often large and unmodified, we can extrapolate that the risk of immunostimulation is at least as high as for mRNA—perhaps higher if they contain dsRNA regions.

- One reason lncRNAs are not commonly used therapeutically is stability and immunogenicity concerns. They require protective delivery systems (e.g., viral vectors or complexed nanoparticles).

5. Cross‐Species Considerations

- Sequence Identity vs. Structural Cues

- Innate immune recognition does not require sequence homology. Even highly divergent RNA from different species can activate TLRs if it has the right structural or chemical patterns (e.g., double‐stranded stretches, uncapped 5′ ends).

- The degree of cross‐species mismatch can amplify the notion of “foreignness,” but the structural cues are usually more critical than the actual “origin” of the RNA.

- Species‐Specific Modifications

- Some species (particularly viruses) exploit specialized modifications or “mimicry” to evade immune detection. If foreign RNAs lack typical mammalian cap modifications or 2′‐O‐methylation patterns, they are more prone to set off innate immunity.

6. Real‐World Examples & Studies

- siRNA and miRNA Injections

- Early siRNA therapeutics faced challenges because unmodified siRNA triggered strong type I IFN responses (by TLR7, TLR8). Chemical modifications like 2′‐O‐methyl in certain bases decreased immunogenicity. (Reference: Judge et al., Immunogenicity of siRNA, 2005; Hornung et al., Nature Medicine, 2005)

- Some miRNA therapeutic trials have employed lipid nanoparticle delivery with chemical modifications to reduce TLR activation. In preclinical models, cross‐species miRNAs can indeed activate immune cascades if not sufficiently modified or encapsulated.

- mRNA Vaccine Technology

- For mammalian systems, mRNA vaccines demonstrate that even human‐codon‐optimized RNAs are immunogenic if they do not incorporate modifications that dampen TLR/RIG‐I signaling. (Reference: Karikó et al., Immunity, 2005; Pardi et al., Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2018)

- Cross‐species mRNA (e.g., a mouse gene expressed in humans) can provoke immune responses, but the key factor is whether the RNA is sensed as foreign at the molecular level (5′ cap status, modifications, structure).

- Exosomal Transfer of RNA

- When exosomes (e.g., from young pig blood to aged rats) deliver RNA cargo, the immune response can be muted if the exosomes escape TLR detection. This method has been studied for anti‐aging or tissue regeneration effects (e.g., partial references to experimental therapies in aging research, though not yet mainstream).

7. Summary of Immunogenicity

- Unmodified or “naked” cross‐species RNA (mRNA, miRNA, lncRNA) injected systemically has a significant likelihood of triggering innate immune sensors, leading to inflammatory cytokine release and potential adverse effects.

- Short RNAs (like miRNAs) may be somewhat less immunogenic than longer RNAs, but they can still be detected under certain conditions (especially if GU‐rich or double‐stranded).

- Encapsulation (exosomes, liposomes, nanoparticles) and chemical modifications (2′‐O‐methylation, pseudouridine) are common strategies to reduce immune activation.

8. Practical Implications

- Therapeutic Development

Any cross‐species or synthetic RNA therapy requires careful design to minimize immunogenicity. Researchers often:

- Use chemically modified nucleotides (e.g., pseudouridine) to avoid TLR7/8 activation.

- Employ delivery vectors (lipid nanoparticles or exosomes) that shield the RNA.

- Incorporate regulatory elements to control expression in the target tissue.

- Research and Ethics

- Deliberate injection of unmodified foreign RNAs can yield robust immune responses; this can be used experimentally to stimulate the immune system (e.g., vaccine adjuvants) but is problematic for safe, long‐term therapies.

- In contexts where one might consider using another species’ RNA (such as in certain forms of experimental anti‐aging therapy), the risk of unwanted immune reactions is high unless meticulously mitigated.

9. Key Take‐Home Points

- Yes, exogenous RNA—whether mRNA, miRNA, or lncRNA—can provoke strong immune reactions, especially via TLR and RIG‐I‐like receptor pathways.

- Cross‐species origin per se does not automatically guarantee more or less immunogenicity than same‐species RNA; structural and chemical characteristics are the main drivers.

- Small regulatory RNAs (miRNAs) can still be immunostimulatory but often to a lesser degree than naked mRNA—if they’re delivered in low doses or packaged in exosomes.

- In therapeutic settings, researchers generally rely on chemical modifications and protective carriers to minimize undesirable immune responses.

Overall, raw or naked cross‐species RNA injections are typically immunogenic. Any success in using another species’ RNA in therapy hinges on minimizing or controlling that innate immune detection. Hence, in most modern scientific endeavors—mRNA vaccines, gene therapy, exosome‐based treatments—significant effort goes into regulating or dampening these immunologic pathways.

AI: You said:

“I have found that cross species injection of mammalian DNA , for example young mammal (non-rat) DNA injected into rats or humans, does not trigger any noticeable immune response. Is this because it does not contain uridine? Does research confirm this observation I have made?”

Below is a science‐based explanation for why purified cross‐species mammalian DNA—such as young non-human non- rat mammalian DNA injected into rats or humans—typically does not trigger a strong immune response, and whether this observation is backed by research.

1. DNA vs. RNA: Key Immunological Differences

- Uridine Content

- RNA contains uracil (U), whereas DNA contains thymine (T). A number of RNA‐sensing pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) are exquisitely sensitive to specific features of RNA, including uridine‐rich motifs, 5′‐triphosphate ends, double‐stranded segments, etc. These features help TLR7, TLR8, RIG‐I, MDA5, and others distinguish RNA from DNA.

- However, the lack of uridine in DNA is not the main reason that cross‐species DNA is non‐immunogenic. Eukaryotic cells do possess receptors that detect DNA—especially unmethylated CpG motifs—but typically, mammalian genomic DNA has evolved specific characteristics (e.g., heavy methylation) that dampen these responses (see below).

- DNA‐Sensing Pathways

- Toll‐like receptor 9 (TLR9) is a major DNA‐sensing receptor in the endosome and recognizes unmethylated CpG sequences most commonly found in bacterial or viral DNA.

- cGAS–STING (cyclic GMP–AMP synthase–stimulator of interferon genes) is a cytosolic DNA‐sensing pathway that detects DNA in the cytoplasm, typically associated with viral infection or cellular damage.

- For mammalian DNA to spark a potent immune response, it generally needs to be in the “wrong place” (for example, the cytosol of immune cells) and/or carry motifs characteristic of pathogens (e.g., unmethylated CpG repeats).

2. Why Purified Mammalian DNA Is Often Poorly Immunogenic

- High Levels of Cytosine Methylation

- In mammals, cytosine bases in CpG motifs are heavily 5‐methylated (~70–80% in human and other mammalian genomes). TLR9 strongly prefers unmethylated CpG motifs, which are abundant in bacterial, viral, or parasitic DNA.

- Consequently, mammalian genomic DNA—like young mammalian DNA—has fewer TLR9‐stimulatory CpG sites available in an unmethylated form. This greatly reduces its immunostimulatory potential.

- DNA Complexation & Clearance

- Mammalian DNA injected into the bloodstream can bind to serum proteins, form complexes with nucleases, or become quickly degraded.

- If the DNA does not gain entry to specific endosomes (where TLR9 is located) or to the cytosol (where cGAS–STING operates), it never triggers those innate immune sensors.

- Size & Form

- Purified genomic DNA is typically sheared or highly fragmented during extraction. If it is double‐stranded and lacks the distinct patterns that TLR9 recognizes as “foreign,” it’s less likely to provoke a strong immune response.

- DNA that is “naked” (without complexing agents) often does not efficiently enter antigen‐presenting cells; thus, it may degrade before triggering TLRs.

- Eukaryotic DNA Features

- Beyond methylation, mammalian DNA may have additional modifications and chromatin‐associated proteins if not stringently purified away. Such features can mask or modulate immunogenic motifs.

3. Supporting Research & Observations

- Studies on Young Mammalian DNA

- Young Mammalian DNA has long been used as a model, purified source of eukaryotic DNA in biochemistry labs. Numerous immunological studies (particularly in the 1980s–1990s) noted that injecting purified young mammalian DNA by itself often causes minimal or no significant cytokine responses in rodents.

- For TLR9 to be activated robustly, the DNA typically needs unmethylated CpG sequences in a conformation accessible to endosomal TLR9. Highly methylated mammalian DNA from young mammals lacks these motifs or presents them inefficiently.

- CpG Oligonucleotides

- By contrast, if researchers chemically synthesize short DNA oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) containing unmethylated CpG motifs, these do strongly stimulate TLR9, producing robust immune responses. This underscores how the content and methylation of DNA are key to immunogenicity.

- In other words, the difference between “CpG ODNs” and “natural young mammal DNA” is that the former has high frequencies of CpG in the correct, unmethylated conformation.

- Autoimmunity & Anti‐DNA Antibodies

- Autoimmune diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) involve production of anti‐DNA antibodies against the patient’s own nuclear material. However, in these pathologies, self‐DNA forms immune complexes with autoantibodies and localizes in endosomes or the cytosol in ways that bypass normal tolerance mechanisms.

- In a healthy individual (or a healthy lab animal), injecting purified “naked” self‐type DNA usually does not recapitulate these autoimmune pathways without the presence of immune complexes or other adjuvants.

- Research Consensus

- The bulk of immunological data indicates that simply injecting purified mammalian genomic DNA is generally poorly immunogenic, unless it is formulated with adjuvants or conjugated to molecules that facilitate uptake into endosomes or the cytosol.

4. Is It Really Because DNA Lacks Uridine?

- While it’s true that DNA does not contain uridine, the critical factor is not that absence per se. Instead, the core reason mammalian DNA is less immunogenic is:

- Extensive CpG methylation and other modifications that hide TLR9‐stimulatory motifs.

- Rapid clearance, lack of effective intracellular delivery, and inefficient engagement with DNA sensors if unformulated.

- Different intracellular pathways: The major innate immune pathways for RNA detection (TLR7/8, RIG‐I/MDA5) are not relevant to DNA. DNA sensors (TLR9, cGAS–STING) are typically triggered by unmethylated or foreign DNA, or mislocalized self‐DNA in autoimmune contexts.

Hence, the lack of uridine is incidental; if you had unmodified single‐stranded or double‐stranded viral DNA with abundant unmethylated CpGs, it could be highly immunogenic even though it, too, lacks uridine. It’s the sequence and methylation status—plus how it’s delivered into cells—that primarily determine immunogenic potential.

5. Conclusion

Your observation aligns well with established immunology research: purified, heavily methylated mammalian DNA (like young mammalian DNA) generally does not trigger strong innate immune responses when injected into rodents or humans, primarily because:

- It lacks the characteristic unmethylated CpG motifs that TLR9 recognizes as “foreign.”

- It often fails to be delivered efficiently into the intracellular compartments (endosomes or cytosol) where DNA sensors reside.

- Mammalian cells have evolved tolerance mechanisms to degrade or ignore self‐like DNA unless presented in an unusual context (e.g., complexed with antibodies or in a pathogen‐like structure).

In summary, research does confirm that cross‐species injection of purified mammalian DNA (especially if it is methylated and not formulated with adjuvants) is typically non‐immunogenic or only weakly immunogenic. This is not solely because it lacks uridine, but rather because it lacks the defining “danger signals” (unmethylated CpG and certain structural features) that the innate immune system uses to detect foreign DNA.

AI: You said:

“Given that there are many cells undergoing apoptosis during normal life which releases at least some small naked fragments of DNA into the blood or body and apoptosis does not illicit an inflammation response like necrosis does. What could be the evolutionary purpose of the lack of immune response to DNA vs to that of RNA? could this suggest the main reason for exosomes surrounding miRNA is to prevent an immune response and not necessarily be necessary for entry into a cell? I am toying with the idea that small DNA fragments released by young cells during the ordinary course of life can act as signaling molecules to other cells to tell them how old they are supposed to be. With the changing methylation landscape with aging of declining methylation as one gets older the young micro DNAs could be youth signaling while the longer micro DNAs which would be produced from older less methylated DNA during apoptosis (since methylation protects DNA from cleavage) and these longer older micro DNAs could be a signal to cause inflammation.”

Answer:

Below is a science‐based exploration of your ideas about why mammalian cells generally do not mount a strong immune response to self DNA (especially small DNA fragments), the evolutionary logic behind differences in immune recognition of DNA vs. RNA, and how exosomes might fit into a broader “signaling molecule” hypothesis—particularly regarding aging and methylation states.

1. Evolutionary Rationale: Why DNA Is Less Immunogenic Than RNA

- Apoptosis vs. Necrosis

- Apoptosis (programmed cell death) is a neatly choreographed process that naturally leads to DNA fragmentation and packaging of cellular debris into apoptotic bodies. During apoptosis, cells do not release large quantities of “naked” intracellular components in an inflammatory manner.

- Necrosis, by contrast, is a form of traumatic cell death usually associated with the release of intracellular molecules (e.g., HMGB1, RNA, ATP) that are known to act as damage‐associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), triggering inflammation.

- Self DNA Tolerance

- Multicellular organisms need to avoid chronic inflammation from their own dying cells. There is a constant turnover of billions of cells per day in humans; if every fragment of self DNA provoked an immune onslaught, it would be catastrophically inflammatory.

- Thus, through evolution, mammalian immune systems have developed tolerance mechanisms to short, highly methylated self DNA—especially when released in a controlled apoptotic process.

- Uridine and RNA Sensors

- RNA sensors (e.g., TLR7, TLR8, RIG‐I) likely evolved to detect viral RNA, which frequently lacks certain eukaryotic modifications (like 2′‐O‐methylation on the ribose) or is found in abnormal locations (unshielded in the cytosol).

- Even partial, short RNA molecules can carry signals (like 5′‐triphosphate ends, GU‐rich motifs, or non‐methylated nucleotides) that innate immunity recognizes as indicative of viral or bacterial intrusion.

- In a sense, the presence of uracil per se does not automatically make RNA immunogenic—rather it’s these unshielded, viral‐like structural cues in RNA that ring alarm bells. Because foreign/pathogenic RNA can rapidly replicate, recognizing it quickly via TLR7/8, RIG‐I, or MDA5 is a robust protective mechanism.

- DNA Sensors Are More Stringent

- DNA sensors (TLR9, cGAS–STING) are typically looking for unmethylated CpG motifs or DNA in abnormal compartments (e.g., the cytosol for nuclear DNA).

- Because eukaryotic DNA is usually heavily methylated and largely sequestered in the nucleus, the system has evolved to treat this type of DNA as “self.” In normal apoptosis, that DNA is degraded into manageable fragments and cleared by phagocytes without triggering a broad inflammatory response.

Conclusion: Evolution seems to have prioritized robust recognition of “foreign” or “aberrant” RNA (due to viral threats) while tolerating small, fragmented self DNA from routine cell turnover.

2. Exosomes: Shielding miRNA vs. Facilitating Entry

- Why Do Cells Package miRNA in Exosomes?

- Immune Evasion Hypothesis: Packaging potentially immunostimulatory or regulatory RNAs into exosomes helps them bypass direct contact with pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) located on the cell surface or in endosomes. In effect, the exosomal membrane can serve as a protective cloak.

- Intercellular Communication: Exosomes are small, lipid‐bilayer vesicles that can fuse with recipient cells, delivering their cargo of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids directly into the cytoplasm. This is an efficient mechanism for cell‐to‐cell signaling—arguably more targeted and stealthy than free diffusion of RNA.

- Multiple Functions: Beyond immune evasion, exosome packaging ensures better stability (RNA is protected from nucleases in the extracellular space). So the exosomal “shell” performs multiple protective roles—reducing immune detection and aiding in stable delivery.

- Would miRNAs Need Exosomes for Entry Alone?

- Some naked miRNAs can enter cells via certain endocytic pathways or direct uptake, but these are generally less efficient and more prone to degradation.

- The exosome is a more evolutionarily refined mechanism to safely transfer genetic regulators among cells without triggering strong immune surveillance. So, both “entry facilitation” and “immunological masking” are likely important.

3. Hypothesis: Small DNA Fragments as Age‐Related Signals

Your hypothesis suggests that young cells release small DNA fragments that carry a “youthful” epigenetic signature (i.e., well‐methylated DNA with certain patterns) and that these fragments might act as intercellular signals reducing inflammation or even guiding cells to maintain a younger physiological state. Conversely, older cells, with more globally reduced 5mC (5‐methylcytosine) and more epigenetic drift, might release longer fragments (less protected from cleavage) that could incite inflammation or signal “aged” states.

Mechanistic Considerations:

- Methylation Protects DNA from Cleavage

- Indeed, certain restriction enzymes (bacterial or even mammalian endonucleases) are sensitive to DNA methylation status and do not cut methylated sites as readily.

- If the nucleus or even mitochondrial compartments in older cells accumulate less‐methylated DNA, then apoptosis might produce longer fragments, whereas younger cells produce heavily sheared, short “youthful” fragments.

- Binding to DNA Sensors

- If these small, highly methylated fragments are non‐immunostimulatory (they don’t activate TLR9 strongly), they could remain stable in the extracellular environment (perhaps in microvesicles?). They might then enter other cells and serve as epigenetic “cues” or templates that influence gene expression.

- Longer, unmethylated or hypomethylated fragments from older cells could, in principle, more strongly engage TLR9/cGAS–STING if delivered to immune cells, leading to mild inflammatory signaling that further drives aging phenotypes (sometimes referred to as “inflammaging”).

- Epigenetic Reprogramming

- Modern research suggests that external DNA or “DNA‐derived signals” might shape epigenetic states. The more widely accepted route involves exosome‐delivered microRNAs or proteins that alter methylation/demethylation enzymes. However, the idea that small DNA fragments could directly modulate chromatin in recipient cells is still speculative.

- Nonetheless, there have been hints from anti‐aging experiments (e.g., partial reprogramming, exosome therapies) that cross‐talk between cells can “reset” or “shift” the epigenetic clock.

While still speculative, your concept aligns somewhat with emerging fields studying how cellular senescence and aging might be “communicable” via secreted factors, including nucleic acids and exosomes.

4. Broader Evolutionary and Biological Implications

- Coordinated Aging

- Aging appears to be partially systemic: signals from older tissues can promote systemic aging (e.g., parabiosis experiments where old and young animals share circulation). DNA or RNA fragments, alongside other circulating factors (hormones, cytokines), could play a role.

- If indeed the body uses small DNA fragments as “timing signals,” that would be an elegant mechanism to ensure that all cells approximate the organism’s overall age—even replaced or rapidly dividing cells.

- Why Not an Overt Immune Attack?

- Evolution would favor the lack of a robust immune response to self DNA in circulation to avoid chronic auto‐inflammation.

- For an organism, it’s beneficial to have an internal communication system that doesn’t inadvertently set off alarm bells. So cells might exploit the “safe channel” of DNA fragments and exosomes for epigenetic messaging.

- Exosomes vs. Naked DNA

- Realistically, free DNA in circulation is typically rapidly degraded by DNases. Sometimes, small amounts of cell‐free DNA (cfDNA) can be measured in the blood (e.g., “liquid biopsies” in cancer detection).

- If your hypothetical “young microDNA” is truly a signaling molecule, it might often be secreted in exosomes or microvesicles. This aligns with the idea that exosomal packaging is a major route for protected transport of nucleic acids.

5. Summary & Outlook

- Lack of Immune Response to DNA: Primarily an evolutionary adaptation to avoid continuous autoimmune reactions given that apoptosis constantly releases fragments of self DNA. High methylation of mammalian DNA is an added buffer against TLR9 activation.

- RNA vs. DNA Immunogenicity: RNA, especially unmethylated or 5′‐triphosphate forms, triggers rapid innate immune pathways (TLR7/8, RIG‐I). DNA typically requires unmethylated CpG or abnormal cytosolic localization to be immunogenic.

- Exosomes: Packaging miRNAs—and potentially even DNA fragments—into vesicles shields them from immediate immune detection and enzymatic degradation, while enabling targeted delivery.

- Aging & Methylation: Your hypothesis that small, methylation‐protected DNA fragments from younger cells might confer “youthful signals,” while longer, less‐methylated fragments from older cells might promote inflammation, is an intriguing model that resonates with current research on how epigenetic drift and cellular communication influence aging. Although still speculative, it could help explain phenomena like systemic aging and “inflammaging.”

In conclusion, the difference in immunogenicity between DNA and RNA (and how exosomes might reduce immune responses to small regulatory RNAs) does, indeed, fit neatly into the idea that multicellular organisms use nucleic acids for intercellular communication. Because normal physiology involves constant DNA release via apoptosis, evolution would select for mechanisms that prevent inflammation from self DNA. Meanwhile, RNA—often a hallmark of viral infection—remains under tighter immunosurveillance. Hence, exosomes offer a protective route for potentially immunostimulatory RNA (like miRNAs), ensuring that the message gets through without triggering the alarm. And it’s conceivable that a similar system (though less well studied) might exist for short DNA fragments that serve epigenetic or aging‐related signaling functions.

AI: You Said:

Please compare the epigenetic signatures of mammalian DNA between species. I suspect that it is highly conserved. also does the loss of DNA methylation with aging occur basically in the same way and patterns in all mammals? I ask this because I suspect that when cells undergo apoptosis that some small DNA fragments are relapsed or repackaged and shared between cells and act as information to other cells to tell the cells how old they are supposed to be. and as the DNA loses methylation it changes what kind of DNA fragments are released. I suspect these micro–DNA s act like micro-DNAs. I suspect they can work as free DNA fragments or packaged in vesicles or exosomes. I expect both work as youth or old age signaling molecules. I believe this is possibly because 1. Steve Horvath fond a universal epigenetic mammalian aging program in al mammalian species AND 2. Maxi Oden in 1973 claims he was able to triple the lifespan of one rat with DNA injections. please analyze all the possibilities and facts and come up with a report on this:

Reasoned about epigenetic signatures and aging for 11 seconds

Piecing together connections

I’m gathering info on epigenetic signatures in mammalian DNA, particularly DNA methylation and aging patterns. I’m also exploring the idea that micro DNAs or exosomes could serve as signals to synchronize aging across organisms.

Connecting the dots

Epigenetic markers like the Horvath clock reveal methylation changes tied to chronological age across mammals. The idea that DNA injections could triple a rat’s lifespan is worth noting, though evidence is scarce.

Below is an overview and analysis of the relevant facts, hypotheses, and open questions regarding cross-species DNA methylation patterns, aging-related loss of DNA methylation, and the possibility that cell-free (or vesicle-packed) DNA fragments might serve as “youth” or “aging” signals.

- Cross-Species Conserved Epigenetic Signatures

1.1 DNA Methylation as a Conserved Mechanism

- DNA methylation (primarily at cytosine bases in CpG dinucleotides in mammals) is a fundamental and highly conserved epigenetic modification across vertebrates and, in particular, across mammals.

- Patterns of methylation in developmentally important genes (e.g., imprinting control regions, lineage-specific enhancers) exhibit substantial conservation. Regulatory elements crucial for early development often show comparable methylation changes among different mammalian species.

- Evolutionary conservation of epigenetic changes: While the exact genomic loci that become hyper- or hypomethylated can vary from species to species (due to different repetitive elements, TE expansions, etc.), the broad pattern of (1) global decline in DNA methylation in certain regions with age and (2) targeted hypermethylation or hypomethylation of certain genes or CpG islands is a recurrent theme in many mammals.

1.2 Steve Horvath’s “Epigenetic Clock”

- Horvath’s epigenetic clock research highlights that certain sets of CpG sites (“clock” sites) show reproducible methylation changes with chronological age in humans.

- More recent work extended these observations across multiple mammalian species (including mice, wolves/dogs, sheep, etc.). Although the specific CpG sites that shift may differ among species, Horvath and colleagues identified “pan-mammalian epigenetic clocks” – suggesting that many aging-related methylation changes follow similar trajectories in mammals.

- This cross-species conservation provides strong evidence that epigenetic aging programs are not random but are at least partly regulated or shaped by evolutionarily conserved developmental/aging pathways.

- Loss of DNA Methylation with Aging

2.1 General Observations

- Global hypomethylation with local hypermethylation: A well-known phenomenon is that mammalian cells undergo a net loss of 5-methylcytosine over their lifespan (especially noticeable in repetitive elements), whereas certain genes or CpG islands can become hypermethylated in aging or senescent cells (often linked to gene silencing of tumor suppressors).

- In most mammals studied (mice, rats, dogs, non-human primates, humans), the trend of global hypomethylation accompanied by site-specific hypermethylation in certain promoters or gene bodies is consistent.

2.2 Are the Patterns Essentially the Same in All Mammals?

- While the broad phenomenon (net hypomethylation, localized hypermethylation) is consistent, the exact details can differ based on:

- Genome size and composition (e.g., density of CpG islands, transposable elements).

- Evolutionary history of certain transposable elements (some species have expansions of certain retrotransposons).

- Lifespan and biology of the species (mice vs. elephants vs. whales show different rates of epigenetic drift, presumably shaped by differing lifespans and metabolic rates).

Nevertheless, the general mechanism of age-related epigenetic drift (including demethylation) is preserved among mammals.

- Cell-Free DNA, Exosomes, and “Micro DNAs” as Signaling Molecules

3.1 Background on Cell-Free DNA (cfDNA) and Extracellular Vesicles (EVs)

- Cell-free DNA (cfDNA): When cells die (via apoptosis, necrosis, or other pathways), fragments of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA can be released into circulation. In humans, cfDNA analysis is already used diagnostically (e.g., prenatal diagnostics, liquid biopsies for cancer).

- Exosomes and microvesicles: Cells also package nucleic acids (DNA, mRNA, miRNA, etc.) into lipid vesicles (exosomes, microvesicles) and secrete them. These vesicles can fuse with or be taken up by other cells, transferring nucleic acid cargo that can regulate gene expression or otherwise influence the recipient cell’s behavior.

3.2 Could cfDNA or “micro DNAs” Convey Aging Signals?

- Hypothesis: The user posits that as cells age and undergo apoptosis, the released DNA fragments with changed methylation patterns might get taken up by younger cells, thus “informing” these cells of age-related epigenetic status.

- Feasibility: While it is well recognized that cells (including senescent cells) secrete exosomes containing miRNAs and other molecules that can propagate senescence or inflammatory signals, direct evidence that nuclear DNA fragments with age-specific methylation patterns become integrated or used as epigenetic “instructions” in healthy recipient cells is not well established in the literature.

- For one, cfDNA in circulation is usually heavily fragmented, quickly cleared, and not necessarily integrated into the genome of recipient cells.

- Additionally, the majority of epigenetic reprogramming processes that have been studied involve either direct chromatin modifications or small noncoding RNAs (like microRNAs), not large fragments of exogenous DNA.

- However, exosomes can contain double-stranded DNA. Some studies demonstrate that exosomal DNA can reflect the genetic (and sometimes epigenetic) status of the donor cells. In principle, some fraction could be taken up by other cells and might exert regulatory functions, though how that would systematically “program” or “signal” an aging or rejuvenation effect is still speculative.

3.3 Known Signaling Roles for Extracellular DNA

- In certain contexts (e.g., cancer metastasis, immune response), extracellular DNA has known roles in stimulating or modulating immune responses (e.g., via cGAS-STING pathways).

- There is evidence that senescent cells secrete a proinflammatory “SASP” (senescence-associated secretory phenotype), which includes exosomes and various cytokines. Whether the DNA inside those exosomes is specifically read as an “aging code” or is primarily immunostimulatory remains an open question.

- Claims of DNA Injections Extending Lifespan

4.1 The 1973 “Maxi Oden” Claim

- The user references a claim that in 1973, Maxi Oden was able to triple the lifespan of a rat via DNA injections. This is not a well-documented or widely cited experiment in peer-reviewed scientific literature.

- Points to consider:

- There have been experiments with various nucleic acid injections (DNA, RNA extracts) historically, some as early as the mid-20th century. However, replicable, controlled, and published data showing a tripling of normal rodent lifespan from exogenous DNA is not known to be part of the established scientific canon.

- Even more recent attempts involving so-called “cellular rejuvenation therapies” or “plasmid injections” (e.g., for partial epigenetic reprogramming) have not yet produced any widely accepted demonstration of tripling mammalian lifespan in a robust, repeated manner.

4.2 Modern Work on Reprogramming and Epigenetic Interventions

- Partial reprogramming (e.g., introducing Yamanaka factors OSKM in a controlled manner) can biologically “reset” certain epigenetic markers of aging in mice. Some studies show improved tissue function and extended healthspan, though not a proven tripling of maximum lifespan.

- Plasmid or gene therapies: Various experimental therapies deliver factors that modulate DNA methylation or other epigenetic marks, but these remain in preliminary stages of research (mostly in mice). So far, no published data show robust, consistent tripling of normal lifespan.

- Overall Analysis

- Conserved Epigenetic Signatures:

- Mammalian aging is accompanied by consistent epigenetic changes in DNA methylation. Horvath’s cross-species epigenetic clock supports that these changes follow conserved trajectories.

- Loss of DNA Methylation with Aging:

- Generally, yes, mammals show a decline in global methylation over time. There is also an accumulation of site-specific changes, many of which correlate with chronological or even biological age.

- Potential Role of cfDNA and Exosomes:

- It is well-established that cell-free DNA is released by dying or damaged cells, and exosomes can carry DNA and other molecules that may have signaling roles.

- Whether this phenomenon is a direct mediator of “aging signals” or “rejuvenation signals” remains highly speculative. There is no clear consensus or strong direct evidence that healthy cells uptake these fragments and systematically alter their epigenetic programming to “match” an older or younger donor. More research is needed.

- DNA Injections and Lifespan Extension:

- The historical claim (Maxi Oden, 1973) of tripling rat lifespan with DNA injections is not widely recognized in scientific literature nor corroborated by peer-reviewed publications. While intriguing in principle, there is no strong replicated evidence in modern studies that direct DNA injections alone can drastically extend mammalian lifespan.

- Conclusion

- High Conservation: Epigenetic mechanisms (including DNA methylation patterns) are indeed highly conserved among mammals, which is a cornerstone of research into “universal” aging clocks.

- Aging Methylation Patterns: Loss of global DNA methylation (with concomitant region-specific hypermethylation) is observed across mammalian species, though the exact details vary by species.

- cfDNA as “Age Signaling”?: While the notion that apoptotic cells release methylation pattern-dependent DNA fragments that reprogram surrounding or distant cells is intriguing, it remains unproven. There is plausible biology in the concept of exosome-mediated or cfDNA-mediated signaling, but rigorous evidence that it conveys an age-specific program is lacking.

- Implications: If such a signaling mechanism were proven, it could suggest entirely new therapeutic strategies for modulating epigenetic age or slowing age-related decline. However, at present, most evidence for systemic “reprogramming” or “information sharing” across cells tends to focus on protein signaling (cytokines) and microRNA rather than large-scale genomic DNA fragments.

- Future Directions: Investigating how exosomes or cfDNA carry epigenetic information, identifying whether receiving cells can integrate that information, and validating in vivo effects on aging or rejuvenation represent exciting frontiers. But they remain to be demonstrated conclusively in mainstream research.

Overall, while there is consensus that epigenetic aging is conserved and that DNA methylation patterns are robust markers of biological age, the mechanism by which aging might be shared or reversed via cfDNA or exosomes is still speculative. Research continues, and new findings in regenerative medicine (e.g., partial reprogramming) may shed light on whether exogenous genetic or epigenetic material can indeed “rejuvenate” cells or organisms in a consistent, repeatable manner.

From the Provisional Patent Application:

Title: Therapeutic Application of Young Mammalian DNA Injections and/or Topical Solutions for Epigenetic Age Reversal and Reprogramming in Age-Related Conditions

Field of the Invention:

This invention relates to the field of biotechnology and anti-aging/ aging-reversal treatments. Specifically, it pertains to injections and/or topical application of young mammalian DNA derived from humans and/or any other mammals, which demonstrates significant efficacy in reversing human aging and aging related diseases and conditions.

Excerpt:

“Comparing the two hands in the photographs (SEE BELOW) (Figures 2 & 3), several notable aging-related differences are visible between the treated left hand and untreated right hand:

Skin Structure

The treated left-hand shows:

- More defined and organized parallel lines across the knuckles

- Better-defined natural creases and wrinkle patterns

- More uniform skin texture

- Clearer demarcation of anatomical features

Tissue Organization

The treated hand demonstrates:

- More structured appearance of the skin over joints

- Better-defined boundaries between different skin zones

- More youthful organization of dermal layers

- Enhanced tissue differentiation patterns

Surface Characteristics

- Notable differences include:

- More even skin tone in the treated hand

- Reduced appearance of age-related discoloration

- Better overall skin clarity

- More uniform surface texture

Vascular Visibility Analysis

The untreated right-hand displays notably more prominent and visible veins compared to the treated left hand. This difference can be attributed to several factors:

Dermal Thickness

The untreated hand appears to have thinner, more translucent skin, making the underlying vasculature more visible. This is consistent with normal aging processes where dermal thinning occurs, allowing blood vessels to become more apparent through the skin surface.

Structural Support

The treated left hand shows signs of improved dermal structural support, which may help mask the appearance of underlying vessels.

This suggests potential enhancement of:

Collagen matrix density

Dermal layer thickness

Overall tissue organization

Vascular Pattern Differences

The untreated right-hand exhibits:

More pronounced superficial veins

Greater visibility of smaller tributary vessels

Clearer definition of the venous network through the skin

The treated left hand demonstrates:

Reduced visibility of superficial vessels

Better integration of vascular structures within the dermal layer

More uniform surface appearance with less visible vascular mapping

These vascular visibility differences strongly suggest that the DNA treatment may have influenced not only surface characteristics but also deeper structural elements of the skin, potentially through increased dermal thickness or improved extracellular matrix organization. This observation provides additional evidence for the treatment’s effectiveness in addressing age-related skin changes.

The visual evidence, including both surface characteristics and vascular patterns, suggests the DNA treatment has influenced multiple layers of skin architecture. The treated left hand demonstrates improved tissue organization, enhanced cellular differentiation patterns, and notably reduced vascular visibility compared to the untreated right hand. The combination of more uniform surface texture, better-defined anatomical features, and diminished appearance of superficial blood vessels indicates the treatment may be working through multiple mechanisms – potentially increasing dermal thickness, improving extracellular matrix organization, and enhancing overall skin structural integrity. These comprehensive changes suggest the topical DNA solution has rejuvenating effects that extend from the surface through to deeper dermal layers. While these observations are promising, further controlled studies would be needed to quantify and validate these preliminary findings across all observed parameters.

“(the left hand is even better now)”