The Four Horsemen of Aging:

How 4 Evolved Mammalian Aging Systems

Reveal the Missing Half of Evolution

Published Online 1/28/2025

Jeff T. Bowles

Lifespan BioResearch LLC

Public Disclosure and Patent Notice

Date of Publication: 1/28/2025

By publishing the following ideas, methods, and inventions on https://JeffTbowles.com, I (Jeff T. Bowles) am making a public disclosure of these concepts. This disclosure establishes “prior art” that may bar others from obtaining valid patent protection for these ideas in many countries worldwide.

Certain jurisdictions—including, but not limited to, the United States, Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Philippines, Australia, South Korea, and Japan—offer a one-year “grace period.” In these countries, an inventor may still be able to file a patent application on the disclosed concepts within one year from the date of this publication. If you are interested in pursuing patent protection in these or any other grace-period jurisdictions in collaboration with me, please contact me at Jeffbo@aol.com to discuss potential arrangements under reasonable terms. Please see list of potential patents at the end of this document.

Abstract

A growing body of evidence challenges the conventional view that aging is merely an accidental byproduct of essential genes and metabolic processes. Instead, this paper revisits a long-overlooked 1998 hypothesis that posited aging is modular—composed of multiple, independently evolved systems that each co-opt the vulnerabilities of the last. Fresh insights are developed concerning short LARP1 (Horvath’s #1 pro-aging gene with an unusual RNA binding site on the protein) a scarcely studied nuclear lncRNA that likely truncates ATM and XP/CS mRNAs and downregulates/prevents the production of WRN by interfering with mRNA spliceosome functions. From these insights, how aging proceeds in at least four evolutionary waves is revealed. System #1 (plant-like vascular/structural decline) appears vestigial in humans, overshadowed/co-opted by Horvath’s universal epigenetic clock. System #2 centers on mitochondrial dysfunction in motile organisms. System #3, tied to advanced DNA repair and immune function, propels progeroid syndromes such as ataxia telangiectasia Cockayne syndrome, and xeroderma pigmentosum. Finally, system #4—emerging alongside sexual reproduction—dominates in Werner’s syndrome, unifying older pathways with newfound genomic instability.

In highlighting short LARP1’s proposed ability to sabotage crucial mRNA splicing leading to defective repair and structural proteins, a surprising synergy is illuminated: these sequentially-evolved senescence pathways act less like random breakdowns and more like a deliberate “orchestra” of aging. Each system is associated with one of the canonical Yamanaka factors (KLF4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Oct4), underscoring the developmental roots of senescence. Far from dismissing aging as a mere trade-off under antagonistic pleiotropy, new evidence is presented consistent with an evolutionarily conserved program—one that likely offers local species-level benefits in predator-rich ecosystems by preserving genetic and phenotypic diversity by preventing excessive, homogenizing contributions to the gene pool by single individuals. The same selection pressure also selects for menopause in humans and declining fertility in animals with aging. Interestingly, the same evolutionary logic that explains aging’s adaptive role applies to the advantage of sexual over asexual reproduction, as sexual reproduction further accelerates genetic (via recombination) and phenotypic diversity and bolsters resilience against evolving predators. For gerontologists, evolutionary theorists, and epigenetic researchers alike, this framework suggests that aging emerges from deeply adaptive, ancient, multi-layered processes rather than serendipitous decline, opening avenues for therapeutic disruption and a deeper understanding of life’s final act.

Introduction

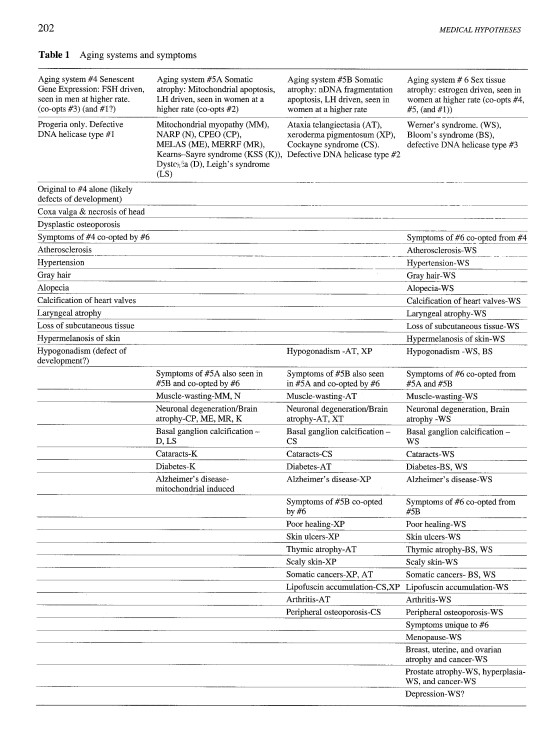

The 1998 paper “The Evolution of Aging-A New Approach to an Old Problem of Biology” proposed that aging comprises several independently evolved “modules” or systems that co-opt one another to drive senescence in a coordinated manner. A summary table that appeared in that 1998 paper appears at the end of this article. In this view, older, foundational aging systems are taken over by newer, specialized mechanisms to ensure a more comprehensive decline. The short LARP1 isoform—a virtually unstudied nuclear long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) with a very unusual mRNA binding motif —is hypothesized to be a central player in orchestrating such co-option by inhibiting or truncating critical DNA repair and structural proteins (WRN, ATM, XP/CS), by altering or inhibiting their mRNA, ultimately accelerating cellular and organismal aging.

In addition to the 4 aging modules, an additional aging system likely evolved first, telomere shortening, when circular plasmid DNA in ancient single cell organisms was forced into a linear pattern that then caused telomere shortening during every round of cell division, but that will not be addressed in this article but can be referred to as aging system #0.

Also, in that 1998 paper, aging was proposed to be controlled by 5mC DNA methylation, to be programmed, and to be driven by the same bio-machinery that drives development. These ideas will only be partially touched upon in this article. The 1998 paper’s 5mC / aging connection preceded Horvath’s serendipitous discovery of the 5mC DNA methylation clock by about 15 years.

Below, are outlined four major aging systems, each associated with different evolutionary origins and distinct sets of pathologies. It is explained how short LARP1 likely blocks normal WRN production (aging system #4) and may simultaneously interfere with the proper splicing of ATM, XP/CS mRNA transcripts (aging system #3). These truncated factors in turn modulate mitochondrial dysfunction (aging system #2) and accelerate vascular/epithelial aging seen in progeria (aging system #1). Finally, each of the canonical Yamanaka factors are mapped to the specific aging system each most potently offsets, highlighting a novel evolutionary perspective wherein aging is actively programmed and selected for in mammals and in many aspects across all species.

Overview of the Four Aging Systems

Aging System #1

Origin/Evolutionary Context: Emerged from very early multicellular ancestors that were closer to plant-like organisms.

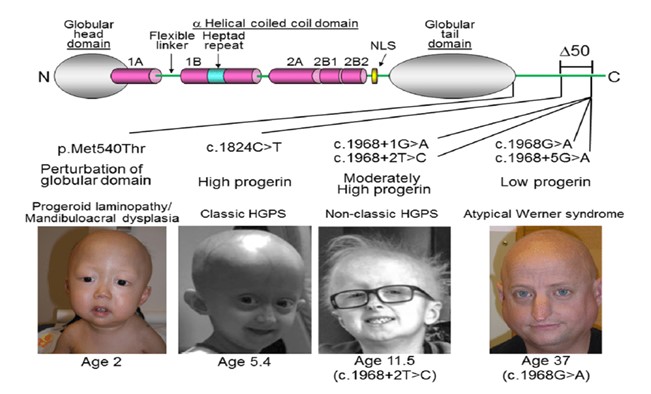

Tissues Most Affected: Vascular-like structures, skin, connective tissue, and the heart—paralleling a rudimentary circulatory system. In accelerated form, this system is seen in Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (progeria), where Lamin A mis-processing severely compromises vascular and connective tissues.

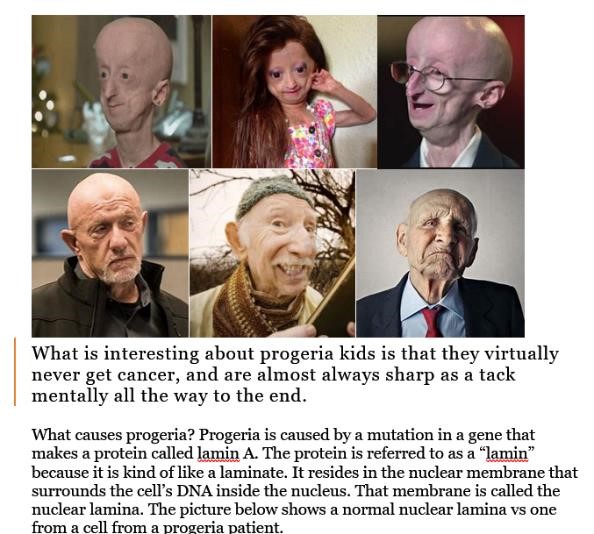

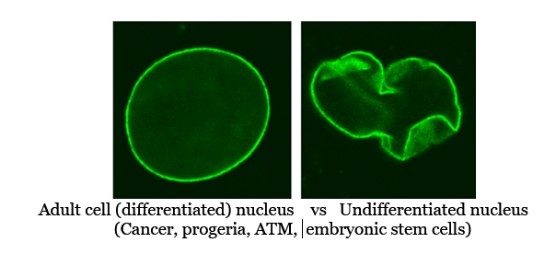

Mechanism: Truncated or mis-spliced structural proteins (e.g., truncated Lamin A aka progerin) lead to loss of cellular differentiation, as Lamin A proteins are involved with large scale gene silencing on the heterochromatin, this leads to loss of cellular differentiation and degradation of vascular integrity and elasticity, calcification, and excess and inappropriate necrosis. This seems to be an aging system that is more associated with male aging than female aging due to males suffering form these pathologies at a higher rate than females. The similarities in appearance of some very old men and progeria patients also point in this direction.

Yamanaka Factor: KLF4, which best rescues or mitigates the “plant-like” structural degenerations associated with system #1.

(Yamanaka factors are assigned to each system by searching the Pub Med database for the particular Yamanaka factor and finding what tissues or diseases each is most highly associated with.)

Note this aging system apparently has become vestigial in humans and has been replaced by the 36+ genes that Horvath found get turned off with aging via DNA methylation of genes that primarily make transcription factors that are used by cells to shut off inappropriate genes by tissue/cell type. This can be seen in the fact that Lamin A proteins are also found to participate in base excision repair processes, and Lamin A’s aging duties apparently were transferred over in evolutionary time to thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG), a base excision repair enzyme that keeps Horvath’s 36+ developmental/transcription factor related genes demethylated and active (it is TDG involved with demethylation of Horvath’s aging related genes not any of the TET enzymes as is currently supposed by many researchers). TDG activity is an AKG dependent enzyme whose activity declines with age as serum , tissue, and cellular AKG levels decline dramatically with aging. When TDG demethylation activities decline, Horvath’s 36+ anti-aging transcription factor related genes get shut down and cells begin to lose their unique cellular identity becoming more like embryonic stem cells. This in effect, is aging caused by cells paradoxically becoming younger (less differentiated) in an unhealthy way.

Aging System #2

Origin/Evolutionary Context: Arose with the evolution of motile animals that use mitochondria-rich muscles, nerves, and sensory organs (eyes, brain).

Tissues Most Affected: Mitochondria-rich tissues—muscles, nerves, and brain. Degeneration here features declining ATP production and increasing ROS.

Mechanism: Properly functioning ATM, and XP/ CS proteins normally enter the mitochondria to curb ROS generation, but truncated forms fail to quench ROS production and thus trigger system #2.

Yamanaka Factor: Sox2, which seems most associated with eye, neuronal and muscle tissues and diseases. Sox2 is also part of the family of genes that contains SRY-the male sex determining gene suggesting the deep association of aging with sexual reproduction.

Aging System #3

Cockayne Syndrome

Xeroderma Pigmentosum-Age 19

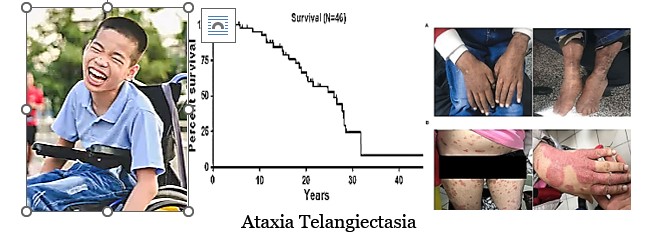

Origin/Evolutionary Context: Coincided with the evolution of advanced DNA repair mechanisms and the modern immune system. This is the first aging system in which cancer appears and seems to be associated with the evolution of apoptosis.

Tissues/Accelerated Forms: Tissues affected by these mutated proteins include major immune system tissues such as thymus, skin, and bone. Ataxia telangiectasia (AT) and Cockayne Syndrome/Xeroderma Pigmentosum (XP/CS) exemplify accelerated aging when the mRNA for these DNA repair proteins (ATM, XP/CS) and thus the proteins themselves are inactivated or truncated. Cockayne Syndrome and Xeroderma Pigmentosum are caused by different truncations of the same helicase protein.

Mechanism: Short LARP1 may directly interfere with splicing of ATM and XP/CS mRNA transcripts. (Or short LARP1 could eliminate the production of WRN which might be required to synthesize fully functional ATM and/or XP/CS proteins-research is needed to answer this question.) When truncated, these proteins fail to properly prevent excess ROS production in the mitochondria (thereby co-opting aging system #2’s mitochondrial ROS production). Truncated ATM and XP/CS proteins also colocalize with the Lamin A mRNA spliceosome causing (deletions or misplicings) in Lamin A mRNA (further co-opting older vulnerabilities, including system #1’s vascular pathologies). One remaining curious fact about this aging system is why cancer is not seen in Cockayne Syndrome. This is not a huge flaw because the protein that is defective in Cockayne Syndrome, when hit with a different mutation gives rise to a large number of cancers in xeroderma pigmentosum.

Yamanaka Factor (YF): c-Myc, which is highly associated with cancer is the YF assigned to aging system #3.

Aging System #4

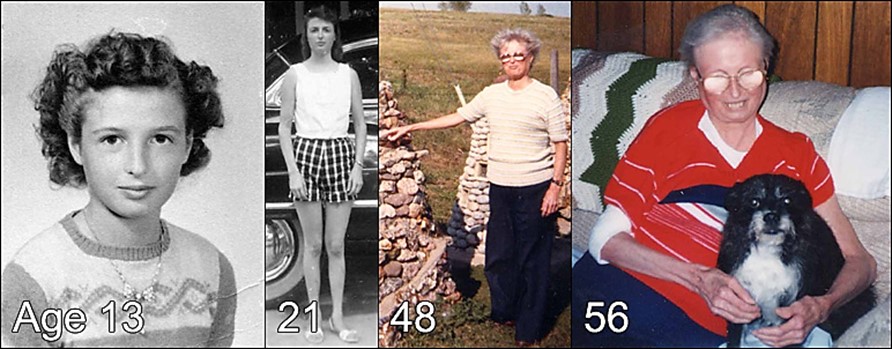

Werner’s Syndrome

Origin/Evolutionary Context: Evolved with the emergence of sexual reproduction, in fact WRN protein does not appear in possibly most of the somatic tissues until puberty is initiated, and WRN protein production is stimulated by a rise in estradiol. The only unique aging features of Werner’s Syndrome are sexual tissue atrophy & sexual tissue cancers, prostate hyperplasia, early menopause and depression (depression suggests some interaction with elevated sex-related MAO-A levels- Interestingly, one of Horvath’s universal aging genes, SP-1 produces a transcription factor that modulates both the initiation of WRN production and binds to MAO-A (and B) promoters). The rest of the symptoms of aging system #4 are all co-opted from aging systems #1 through 3, Aging system #4 is the dominant controlling aging system in this model (this does not account for Horvath’s universal mammalian epigenetic aging system where loss of TDG driven demethylation of 36+ transcription factor related genes seems to replace the Lamin A aging system #1 which seems to have become mostly vestigial in humans. Truncated Lamin A proteins are still seen in some, but not all, aging humans. Horvath’s universal mammalian aging system is expected to also coopt aging system #4 via short LARP1)).

Accelerated Form of Aging System #4: Werner’s syndrome (WS), which recapitulates many phenotypic features of all previously evolved systems. In WS, truncated or missing WRN protein leads to broad genomic instability, loss of stem cell differentiation, faster telomere erosion, and full-spectrum aging pathologies. The helicase function of the WRN helicase is promoted when 6 identical WRN protein subunits coalesce into a donut shape structure. When the WRN protein is truncated, the helicase itself is not likely causing any aging symptoms except for the few rare cancers seen in Werner’s. However most of the aging related functions of WRN are performed by the single WRN subunit protein which has functions related to gene silencing / differentiation in stem cells and other aging related duties.

Mechanism: Short LARP1 is proposed to inhibit WRN production, thus triggering aging system #4, thereby unleashing a “master” version of aging that can incorporate or “commandeer” the downstream aging symptoms of systems #1–3.

Yamanaka Factor: Oct4, has been found by the Bohr lab to interact with WRN in either promoting or repressing H3K4me3.

Although each system can be discussed independently, they are fundamentally interlinked. For example, truncated ATM (system #3) (this also applies to the truncated XP/CS protein as well) not only fosters DNA repair defects but also fails to suppress mitochondrial ROS (system #2), and also colocalizes with the Lamin A spliceosome machinery (system #1). By possibly blocking WRN mRNA and protein production, short LARP1 effectively may weave all prior systems into a unified aging cascade (system #4).

A Four-System Aging Table

Below is a concise table summarizing hypotheses of how each aging system works, its primary accelerated-disease analog, major tissues affected, and associated Yamanaka factor. The table also highlights how newer systems may co-opt older ones.

| Aging System | Origin | Primary Tissues Affected | Pathologies / Accelerated Forms | Truncated or Missing Factors | Yamanaka Factor | Co-Option Strategy |

| #1 | Plant-like ancestors, earliest multicellular life |

“Vascular” tissues: veins, skin, heart |

Progeria Key (Hutchinson-Gilford) |

Lamin A → Progerin | KLF4 | Was Co-opted by truncated or mutated ATM and XP/CS from system #3-now vestigial. Now Coopted by system #4 (WRN) only? |

| #2 | Rise of motile animals (muscles, nerves, eyes) |

High-ATP organs: muscle, brain, eyes, nerves, auditory nerves |

Various Mitochondrial myopathies, neurodegeneration, “movement-based” decline |

Normal ATM/XP/CS → truncated forms fail to limit ROS |

Sox2 |

Receives co-option from system #3’s truncated ATM/XP/CS, generating unbridled ROS. It appears aging system #2 no longer co-opts aging system #1, suggesting this mechanism may have become vestigial. This could explain some gaps in the aging symptoms table presented later. |

| #3 | Complex DNA repair,

Apoptosis, & |

Whole body, especially dividing cells and immune-related tissues |

Ataxia Telangiectasia, Cockayne Syndrome / Xeroderma Pigmentosum (XP/CS) |

ATM, XP, CS → truncated transcripts |

c-Myc | Short LARP1 causes mis-splicing of ATM, XP/CS → triggers system #2 (mitochondria) and likely used to trigger system #1 (vascular/skin).The lack of progeria-like symptoms in #2 and #3 suggests this coopting part of the mechanism is vestigial, for system #1 but #3 still coopts system #2 |

| #4 | Emergence of sexual reproduction |

Multisystemic, recapitulating #1–3 plus sex related tissues & depression-MAO-A which differs in the sexes |

Werner’s syndrome (WRN deficiency) |

WRN → absent or severely truncated |

Oct4 | Horvath’s universal mammalian aging system.-Short LARP1 is expected to block WRN splicing of system #4, thereby co-opting and amplifying all older systems. #1-#3. This serves as a “master” aging system with broad synergy over #1–3. |

Short LARP1’s Pivotal Role in Co-Option

Short LARP1 is a lncRNA isoform localized in the nucleus, where it hypothetically can hijack spliceosome function. By interfering with ATM, XP, CS, and WRN mRNA transcripts, it generates truncated or wholly missing proteins. The proteins of these transcripts once served protective roles—e.g., preventing excessive ROS in mitochondria (system #2) or repairing DNA in dividing cells (system #3). Short LARP1 thus could allow the newly evolved aging systems (#3 and #4) to seize the vulnerabilities introduced by older systems (#1 and #2) and unify them into a robust senescent phenotype. While LARP1 has been found in the Horvath study to be the #1 aging gene that gets turned on with aging in all mammals and almost all tissues, the isoform was not identified. Horvath found no increase in the canonical long LARP1 seen in the cytoplasm with aging. Short LARP1 is relatively unstudied and so far, has only been seen active in the nucleus during embryogenesis and then it disappears. (by Sarah Blagden). Apparently nobody has looked for short LARP1 in senescent cells. Interestingly, a Harvard spliceosome database derived from (very old) Hela cancer cells included LARP1 (isoform unnoted) until the researchers were notified by the author that the canonical form (long LARP1) was not considered a spliceosome related protein and only appeared in the cytoplasm outside of the nucleus. Soon after that, the database was temporarily taken down and when put back up, LARP1 had been removed. The author copied and still retains the original entire Harvard spliceosome protein database that includes LARP1.

Has this happened before?

Yes. Evolution already uses a truncated Lamin A protein (progerin) to induce tissue breakdown during fetal development. In a 2011 study, researchers found:

Progerin was highly expressed (about 16% of cells) in the closing ductus arteriosus (DA), the artery that helps babies transition to breathing air.

Progerin appeared mostly where necrosis and apoptosis occurred. (Inappropriate necrosis is one hallmark of progeria)

Only about 2.5% of cells in the adjacent aorta showed progerin.

Progerin was absent in fetal or non-closing (persistent) DA.

Its presence coincided with reduced Lamin A/C and tissue remodeling.

Bottom line:

During normal fetal development, truncated Lamin A protein aka progerin appears to help “sculpt away” tissue in the DA. Then it largely vanishes in youth, only to reappear in some older individuals where it contributes to aging—much like how short LARP1 is expected to behave, though short LARP1 disappears entirely until expected to be found to appear in later aging.

Two New Insights

- Why Evolution Targets RNA Instead of DNA for Aging

If evolution had selected for aging via targeted DNA damage, it would likely preclude embryonic reprogramming (e.g., SCNT-based cloning) and the partial reversal of senescence seen with intermittent Yamanaka factor exposure. In other words, if the “aging program” were hard-coded in DNA in a way that was irreparable, reversing aging at the epigenetic or RNA-processing level would be effectively impossible. Instead, the data imply that evolutionary aging assaults mRNA or RNA splicing. This approach is less final and allows for potential reversion—thus aligning with observations that adult cells can be rejuvenated into pluripotent states without catastrophic outcomes from permanent DNA-level defects. Short LARP1, by truncating WRN, ATM, and XP/CS transcripts, exemplifies an “RNA-level sabotage” that can be disrupted or reversed in principle.

- How Evolution Protects Short LARP1 from Easy Knockouts

At first glance, one might wonder why a single knockout mutation in short LARP1 has not already removed aging from certain lineages. The answer lies in long LARP1: a large, protein-coding isoform essential for viability. Because short LARP1’s transcript is embedded in or overlaps with the canonical LARP1 locus, a simple knockout of the entire gene would also remove the essential long LARP1—a lethal event. By nesting this “master aging” isoform within a vital gene, evolution prevents an easy genetic “escape hatch” from aging. This structural arrangement reveals how cunningly aging can be preserved as a stable trait despite its drawbacks for individual survival in late life.

- How immortality could evolve over time: One notable feature in the provided aging-syndrome table at the end of this article is the gaps where we would expect aging system #1–type symptoms (e.g., vascular and connective-tissue decline) to appear in either aging system #2 or #3 but do not. For instance, ataxia telangiectasia (system #3) and various mitochondrial pathologies (system #2) do not display the pronounced vascular stiffening or rapid atherosclerosis typical of progeria (system #1); instead, the progeroid elements in AT or mitochondrial disorders focus more on immune or neuromuscular dysfunction. Interestingly, Lamin A–related nuclear defects seem at play in both progeria and ataxia telangiectasia, progeric nuclei appear abnormally flexible and misshapen, AT nuclei can be too flexible and misshapen, suggesting Lamin A’s normal “tensing” or “stiffening” role is compromised in both diseases. Yet, the aging symptoms seen in progeria seem to have been lost to aging system #3. These gaps in symptoms highlight the possibility that, as newer aging systems emerge and then evolve (e.g., #3 and #4), they may initially co-opt all vulnerabilities of the earlier modules, but losing cooption of some or all of them over time. In an evolutionary sense, one can imagine a future in which all vestigial aging pathways are bypassed or “knocked out,” allowing certain lineages to trend toward non-aging phenotypes. Over maybe millions of years, this can be viewed as a blueprint for how species might gradually lose entire layers of senescence, ultimately converging on an organism that avoids most, if not all, of the pathologies cataloged in these aging systems.

More Aging Systems Evolving:

Recent findings indicate that newer layers of aging machinery have continued to evolve and graft themselves onto the four existing systems, further intensifying late-life decline. For instance, work by Lorna Harries points to AKT–FOXO1 and ERK–ETV6 as recently evolved pathways capable of inducing mRNA splicing errors under stress—much like truncated ATM, XP/CS, or WRN disrupt DNA repair. FOXO1, long recognized for its role in insulin/IGF longevity signaling, also influences alternative splicing when it accumulates in the nucleus, while ERK–ETV6 can spur oncogenic transformation and spliceosomal dysfunction. At the same time, MAO-A and MAO-B, two FAD-dependent “death genes,” surge with age, depleting FAD in a manner parallel to how CD38 siphons off NAD+, both of which erode mitochondrial energy (system #2). Notably, SP-1—one of Horvath’s universal aging genes—binds the promoters of both MAO-A and MAO-B and is also involved in WRN transcription at puberty, thereby linking the sexual/reproductive axis (system #4) to these emerging pro-senescence enzymes. Meanwhile, PAX5, another Horvath aging related gene, appears to upregulate CD38 with age, magnifying the overall mitochondrial collapse. Finally, truncated ATM (owing to short LARP1 mis-splicing) may misdirect kinases such as AKT and ERK, which in turn misregulate FOXO1 and ETV6, creating an additional “fifth wave” of splicing defects. Taken together, these interlocking factors—SP-1, PAX5, MAO isoforms, and mis-phosphorylated AKT/ERK cascades—further co-opt the original aging systems by uniting sex-specific vulnerabilities (system #4) with cofactor depletion (system #2) and DNA repair breakdowns (system #3), underscoring how successive generations of senescence mechanisms cross-activate and amplify one another.

The Place of miR-128 and Other “Death genes”

Although not the focus here, it is worth noting that miR-128 (sometimes dubbed a “pure death gene”) may further aggravate these aging systems by binding to and inactivating protective mRNA transcripts in older cells. It appears to have negligible early-life effects, consistent with a gene product whose sole function is promoting senescence. MAO-B also appears to be a pure “death gene” as proposed by the author in another paper with little to no negative early life phenotype effects upon knockout. Late life dramatic increases in MAO-B are associated with a long list of devastating pathologies from Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s to cancer. MAO-B knockout mice are 100% protected from Parkinson’s disease, for example.

Evidence for Evolutionary Selection of Aging

These findings counter the classical notion that aging is purely an accidental byproduct of essential genes gone awry. Instead, each successive system builds upon earlier ones, with short LARP1 likely orchestrating a full-spectrum deterioration in advanced age. The synergy between the four aging systems—plus the correlation with limiting reproduction by single individuals in sexually reproducing species—supports a hypothesis that aging was favored by selection, possibly for population local species-level benefits.

How might species selection for aging work? It would happen on a local ecosystem basis where local non aging groups have lower genetic/phenotypic diversity than aging local groups. An evolving predator can completely kill off a group of more identical individuals that have lower genetic diversity than a more diverse group. Diversity can be lost by the excess contribution to the gene pool by smaller numbers of individuals, thus providing an advantage to limiting any one individual’s reproduction via aging. It would be harder for an evolving predator to kill all of the members of a more diverse group. This leads to a higher likelihood of a few survivors who can reconstitute the group with more predator-protected genes. How does aging spread? Local surviving aging groups of say aging/sexual rabbits will migrate to other ecosystems and replace say non-aging ground squirrels that went extinct at that location. Under this model, aging is being selected for almost everywhere all the time at the local species level but it is very hard to see. The same logic applies to the evolution and existence of sexual reproduction but with a focus of accelerating the creation of genetic and phenotypic diversity rather than protecting its decline. Sexual reproduction allows a much more rapid production and selecting for positive and culling of various negative genetic combinations/mutations/phenotypes than could occur in asexually reproducing species by many orders of magnitude. This model also allows for what is seen in the real world- the rare existence of non-aging and asexually reproducing animals usually found in isolated environments or who have evolved perfect predator defense. According to mainstream selfish gene theory, asexual non-aging organisms should be the norm.

What might we consider a perfect predator defense? Flight (birds /bats) full body armor (tortoises/clams/lobsters), extreme (relatively) intelligence (humans / apes), and isolation (deep dwelling fish /sea creatures, artic dwellers, cave dwelling animals). Many animals with these adaptations or life habits have exceptionally long lifespans based on that expected by their body size. What if there is no perfect predator defense available? Two of the last three on the list are diversity, and speed of evolution. Which are maintained by sexual reproduction and aging. With enough diversity along with accelerated evolution, prey species have at least a reasonable chance of surviving evolving predators. And to boost the chances even higher evolution created male and female sex types, where females tend to be protected while males with bright colors and loud songs, attract predators to test their fitness. Male sex types are the final defense to evolving predation on the list of defenses. These sacrificial males allow the gene pool to be cleansed of predator ineffective genes. This often occurs when brightly colored, crazy dancing, or loud males attract predators, as well as females. The males that survive predator attention get to reproduce in large numbers with many females. As Mel Brooks once said:” It’s good to be the king!”. This raises some interesting questions:

- Could this evolutionary pressure be the reason that human societies so often organize themselves into monarchies so similar to bee hives and ant colonies and why “God save the queen” (or king) is a common refrain of the unwashed masses?

- Is the evolutionary purpose of human monarchies to make sure at least one superior mating pair survive catastrophes to reconstitute the group when the danger abates?

- Could this be the evolutionary impetus behind the seeking of power purely for power’s sake by any means necessary by various political systems/parties/personality cults?

- Does this mean that the American experiment of elevating the rights of the individual while diminishing those of the state or the king is eventually doomed to failure?

Some animals and organisms appear to defy the “norm” of aging and sexual reproduction, often thriving in environments where predators are scarce or where they possess near-perfect defenses. For example, quahog clams, bats, Greenland sharks, and Galápagos tortoises can live extraordinarily long lives for their body size, partly because their habitats (deep oceans, protected waters, caves, remote islands) minimize threats and also because some of them are defended by flight or full body armor. Meanwhile, certain species—like female cave crickets, whiptail lizards, and the Brahminy blind snake (a snake that appears identical to the standard earthworm, and lives entirely underground on all habited continents)—reproduce entirely asexually, suggesting that, in isolated, stable, and protected habitats, the need for genetic diversity via mating can be reduced to zero. Other creatures—such as Komodo dragons, boa constrictors, hammerhead sharks, and various fish—can switch to parthenogenesis in the absence of males, preserving their lineages without traditional mating. And a number of species, especially among fish, if there are no males around, the females can switch their sex to male.

However, some birds (e.g., chickens, turkeys, peacocks) have relatively limited defenses against predators but very conspicuous males, which can draw in predators and risk wiping out all local males. In these cases, retaining the ability for females to reproduce asexually offers a fallback against local extinction when all males are lost to predation. In all these scenarios, organisms benefit either from formidable predator defenses (thick shells, venomous bites, flight, remote habitats) or a built-in reproductive backup (parthenogenesis), both of which allow such species to escape the evolutionary pressures that typically drive shorter lifespans and necessitate frequent genetic mixing. If you would like to see a brief summary of my take on how and why aging and sex are selected for please visit the blog post at this link: https://jefftbowles.com/unifying-theory-of-the-evolution-of-aging-sex-via-predator-selection/

It is intersting to consider the predator defensive adaptation of flight: In many island ecosystems free of mammalian predators, birds have repeatedly lost the ability to fly—classic examples include the kiwi in New Zealand, the dodo in Mauritius, and the flightless cormorant in the Galapagos. The prevailing explanation is that flight evolves primarily as an anti-predator strategy, and in the absence of large ground-based threats, maintaining the high metabolic cost of flight (and the anatomical adaptations it requires) confers no advantage. If flight offered a general survival benefit beyond predator avoidance—such as escaping fires, droughts, famines, or migrating to new feeding grounds—these flightless island species would presumably keep it. Even predatory birds can succumb to flightlessness if isolated from threats higher on the food chain (though documented cases in raptors are extremely rare, likely because many hawks and eagles have faced competition or predation pressure in most of their ranges). As for bats, there are no truly flightless species; however, the New Zealand lesser short-tailed bat (Mystacina tuberculata) is notably terrestrial—it retains the capacity for flight but spends considerable time “walking” on the forest floor, a quirk attributed to an ancient environment with few predators. This again underscores the core point: if the cost of flight is not offset by predator-driven selective pressure, gradual loss of flight can occur.

Some programmed aging theorists have proposed that aging evolved to prevent population explosions that could lead to local extinction via exhaustion of the food supply. However, evolution already has this problem covered. When organisms undergo caloric restriction or drought, their melatonin levels increase dramatically which acts as birth control in females as well as males. In fact, 75 mg of melatonin per night was found to be an effective form of birth control for women in the 1990’s in Europe, although that study has been scrubbed of important information and has been hit with an “unreliable” warning from Pub Med having something to do with seasonal animals not being relevant to humans (even though the study was conducted on humans). Sounds like sellers of birth control pills did not like it! The study was titled “Melatonin -Contraceptive for the 90’s” by Silman. In males, very high dose melatonin can dry up semen production to almost nothing and cause erectile dysfunction and diminish any pleasure from sex. (See the side effects of hair loss medications such as Propecia which acts in a similar manner-melatonin boosts progesterone while Proscar is simply a tweaked version of progesterone). So, when food supplies or water are scarce, evolution just stops the group from reproducing, meaning aging is not needed for this purpose to control population size.

If this protection from drought or famine was the driving force behind selection for aging, then one would expect isolated bird species to retain the adaptation of flight to escape famines or droughts. Because this does not happen, we can rule out adaptation to famines and droughts as a driving force for the selection of flight and aging. We are let with only one force that selects for both aging and flight (and sex) – evolving predation.

Conclusion

Building upon the original 1998 proposal that aging consists of multiple, independently evolved modules, we now see a more comprehensive framework in which at least four major aging systems (plus a primordial “system #0” of telomere shortening) evolved in sequence.

System #1 (KLF4, reminiscent of older plant-like multicellular traits),

System #2 (Sox2, associated with mitochondrial changes in motile animals),

System #3 (c-Myc, joined with advanced DNA repair/immune functions),

System #4 (Oct4, culminating in broad senescence once sexual reproduction became established).

Each system reflects a different stage of evolutionary development/history and is selectively co-opted by newly arising layers of senescence. Aging system #1, which emerged from plant-like ancestors, has become partly vestigial in humans and seemingly replaced by Horvath’s universal mammalian epigenetic aging mechanism that involves the methylation (and demethylation via TDG) of specific developmental transcription factors. Aging system #2 (mitochondrial dysfunction in motile animals) largely affects muscle and neural tissues, while aging system #3 (advanced DNA repair/immune-related pathways) gives rise to the classic progeroid syndromes of ataxia telangiectasia and Cockayne syndrome/xeroderma pigmentosum when truncated ATM or XP/CS proteins fail to properly repair DNA, or suppress ROS or properly regulate Lamin A splicing. Finally, aging system #4 is linked to the emergence of sexual reproduction and the WRN protein, encompassing full-spectrum senescence as exemplified by Werner’s syndrome.

Crucial to this picture is the mostly unstudied short LARP1 isoform, a nuclear lncRNA that likely causes the suppressing, misplicing or truncation of the mRNAs of key protective proteins (ATM, XP/CS, WRN). By doing so, short LARP1 effectively bridges newer aging systems like Horvath’s universal mammalian aging system with earlier evolved aging systems like (#3 and #4) with even older ones (#1 and #2), ensuring global degradation and aging. The synergy among systems explains why certain progeroid syndromes show overlapping phenotypes or can selectively omit features of earlier modules (e.g., the partial vestigiality of system #1).

A key new insight is that short LARP1 likely truncates or sabotages protective mRNA transcripts (WRN, ATM, XP/CS), thereby unifying earlier aging vulnerabilities with more recent ones. Because the short LARP1 isoform is embedded in the vital long LARP1 gene, simple knockouts that might otherwise disable aging are not evolutionarily feasible. This structural arrangement underscores how aging can remain “locked in” as a stable trait despite offering no late-life advantage to individuals.

Another crucial new insight is that evolution has seemingly chosen to target RNA (and its splicing) rather than inflict direct, irreversible damage on the DNA itself. If aging were “hard-coded” by mutating DNA in ways that could not be repaired, then phenomena like somatic cell nuclear transfer (cloning) or experimental partial reprogramming (using Yamanaka factors) would be nearly impossible to achieve. In contrast, by disrupting the RNA level through factors like short LARP1, evolution ensures that aging’s effects remain reversible in principle—offering a powerful mechanism for lineage survival if conditions demand the restoration of youthful phenotypes, such as in germ-line reprogramming or epigenetic resetting.

Beyond mechanistic details, this framework supports the notion that aging was selected for at a species level. More genetically and phenotypically diverse populations—often aging, sexual reproducers—have an adaptive advantage over less diverse, potentially non-aging groups when confronted with evolving predators in local ecosystems. The frequent loss of flight in predator-free island birds is a direct analog to how, in the absence of evolving predators, species can dispense with aging and sexual reproduction over time. Indeed, sexual reproduction accelerates genetic diversity and culls weaker phenotypes by exposing males to predator selection pressure, while aging limits any single individual from dominating the gene pool. Both processes, in this view, serve an ecosystem-level purpose of maintaining population resilience against evolving threats. Thus, aging spreads and persists not through individual-level benefit but via a broader ecological and evolutionary advantage. In this sense, short LARP1’s central role in coordinating the truncation of ATM, XP/CS, and reducing WRN levels provides a striking example of how “death genes” can be integrated with epigenetic regulation and telomere attrition (system #0) to form a unified, adaptive senescence program.

Collectively, these findings point to an evolutionarily conserved, multipronged, and actively maintained aging process. The four core systems—plus the telomere-based system #0—give rise to incremental layers of vulnerability, while short LARP1, Yamanaka factors, and methylation/demethylation machineries offer molecular entry points for therapeutic interventions and deeper evolutionary insights.

The aging symptoms table from the 1998 paper- (a bit ahead of its time?)

If you liked this blog post it continues on with part 2:

check it out>>>

https://jefftbowles.com/ancient-blueprints-of-decline-how-four-evolutionary-waves-over-800-million-years-shaped-the-aging-we-know-today/

Now let’s gather a little evidence:

PLoS One. 2011 Sep 6;6(9):e23975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023975

Differential Temporal and Spatial Progerin Expression during Closure of the Ductus Arteriosus in Neonates

Regina Bökenkamp 1,3,*,#, Vered Raz 2,#, Andrea Venema 2, Marco C DeRuiter 3, Conny van Munsteren 3, Michelle Olive 4, Elizabeth G Nabel 5, Adriana C Gittenberger-de Groot 3

Editor: Rory Edward Morty6

Author information

Article notes

Copyright and License information

PMCID: PMC3167818 PMID: 21915271

This article has been corrected. See PLoS One. 2011 Sep 23;6(9):10.1371/annotation/c0198e87-d087-444c-8be9-780adb1582be.

Abstract

Closure of the ductus arteriosus (DA) at birth is essential for the transition from fetal to postnatal life. Before birth the DA bypasses the uninflated lungs by shunting blood from the pulmonary trunk into the systemic circulation. The molecular mechanism underlying DA closure and degeneration has not been fully elucidated, but is associated with apoptosis and cytolytic necrosis in the inner media and intima. We detected features of histology during DA degeneration that are comparable to Hutchinson Gilford Progeria syndrome and ageing. Immunohistochemistry on human fetal and neonatal DA, and aorta showed that lamin A/C was expressed in all layers of the vessel wall. As a novel finding we report that progerin, a splicing variant of lamin A/C was expressed almost selectively in the normal closing neonatal DA, from which we hypothesized that progerin is involved in DA closure. Progerin was detected in 16.2%±7.2 cells of the DA. Progerin-expressing cells were predominantly located in intima and inner media where cytolytic necrosis accompanied by apoptosis will develop. Concomitantly we found loss of α-smooth muscle actin as well as reduced lamin A/C expression compared to the fetal and non-closing DA. In cells of the adjacent aorta, that remains patent, progerin expression was only sporadically detected in 2.5%±1.5 of the cells. Data were substantiated by the detection of mRNA of progerin in the neonatal DA but not in the aorta, by PCR and sequencing analysis. The fetal DA and the non-closing persistent DA did not present with progerin expressing cells. Our analysis revealed that the spatiotemporal expression of lamin A/C and progerin in the neonatal DA was mutually exclusive. We suggest that activation of LMNA alternative splicing is involved in vascular remodeling in the circulatory system during normal neonatal DA closure.

Cao K, Blair CD, Faddah DA, Kieckhaefer JE, Olive M, Erdos MR, Nabel EG, Collins FS. Progerin and telomere dysfunction collaborate to trigger cellular senescence in normal human fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 2011 Jul;121(7):2833-44. doi: 10.1172/JCI43578. Epub 2011 Jun 13. PMID: 21670498; PMCID: PMC3223815.

Summary:

The study focuses on the interaction between progerin (a toxic protein) and telomeres (protective caps at the ends of chromosomes).

As telomeres shorten during cell division, more progerin is produced, which is associated with age-related cell damage.

Progerin is a mutated version of lamin A, a protein that helps maintain the structure of a cell’s nucleus.

The research shows that telomere shortening alters RNA splicing, affecting the production of progerin and other proteins.

This process occurs in normal aging cells, not just in cells affected by progeria (a rare premature aging disease). The study suggests a link between telomere dysfunction and progerin production in the normal aging process. Cells with a constant supply of telomerase (an enzyme that extends telomeres) produce very little progerin. The researchers conducted tests on normal cells from individuals aged 10 to 92, finding that cells that had divided more times had higher progerin production.

(Does this suggest aging system #0 coopts system #1 as the summary implies or does progerin production cause telomere shortening and thus aging system #1 coopts system #0 as would be indicated in this new model?)The study provides insights into how progerin may contribute to the normal aging process, connecting a rare disease (progeria) to general aging mechanisms. This research offers a new understanding of the relationship between telomeres, progerin, and cellular aging, potentially opening new avenues for studying both premature aging disorders and normal aging processes.

From AI-

Several studies have demonstrated that normal ATM and CS/XP proteins play important roles in mitochondrial function and ROS regulation, while their mutated forms fail to reduce ROS effectively. Here are the key findings from relevant studies:

Normal ATM and CS/XP Proteins in Mitochondrial ROS Regulation

ATM

ATM localizes to mitochondria and acts as a sensor for mitochondrial-derived ROS1.

ATM activation in response to oxidative stress regulates mitochondrial function and turnover4.

ATM promotes the elimination of altered mitochondria via mitophagy, helping to control ROS levels4.

CS/XP Proteins

XPC has been shown to localize to mitochondria and regulate mtDNA integrity2.

CS proteins (CSA and CSB) are involved in mitochondrial base excision repair (BER) and protection from oxidative mtDNA damage.

Mutated ATM and XP/CS Proteins and Excessive ROS

ATM Mutations

A-T cells lacking ATM function show increased metabolic stress, reduced expression of antioxidant genes, and severe dysregulation of ROS.

Loss of ATM’s mitochondrial ROS-sensing function may be responsible for ROS accumulation and oxidative stress in A-T.

XP/CS Mutations

Down-regulation of XPC in human keratinocytes results in increased intracellular ROS levels and mtDNA oxidation6.

CSA-deficient cells show increased mtDNA mutagenesis when exposed to oxidative stress, which can be prevented by antioxidants like vitamin E.

CSB-deficient fibroblasts exhibit higher frequencies of mtDNA mutations, which can be reduced to normal levels by complementation with the wild-type CSB gene.

These studies collectively demonstrate that normal ATM and CS/XP proteins play crucial roles in maintaining mitochondrial function and preventing excessive ROS production. When mutated, these proteins fail to effectively reduce ROS levels, leading to oxidative stress and cellular damage.

ATM and Lamin A Interactions

ATM has been found to regulate Lamin A levels:

ATM inhibition or deletion leads to reduced expression of the nuclear envelope protein lamin A1.

This regulation appears to occur at the transcriptional level, as ATM inhibition or deletion resulted in reduced LMNA mRNA levels1.

ATM and Lamin A are both present in the nucleus:

ATM is uniformly distributed in both the cytoplasm and nucleus, except for the nucleoli10.

Lamin A is a key component of the nuclear lamina and is present at the nuclear periphery and in the nucleoplasm213.

Thought about ATM, CS/XP, and Lamin A for 17 seconds

Below are some starting points in the literature that link ATM, Cockayne Syndrome (CS) / Xeroderma Pigmentosum (XP) proteins, and lamin A (including splicing). Direct, one-to-one studies on “ATM or CS/XP interacting specifically with lamin A splice events” can be sparse, so the following references show how these DNA-repair proteins and lamin A (or its splicing and function) intersect in DNA damage response, genomic stability, and transcription-coupled repair—all processes in which splicing and lamin function are relevant. Where direct lamin A or lamin A splicing details are involved, they’re noted.

- ATM and Lamin A Interactions

Redwood AB, Perkins SM, Vanderwaal RP, et al.

A dual role for A-type lamins in DNA double-strand break repair.

Cell Cycle. 2011;10(15):2549–2560.

Relevance: Shows that lamin A/C is crucial for efficient DNA double-strand break repair. Also indicates that A-type lamins interact functionally with ATM (and other repair factors) to maintain genome stability. While it doesn’t focus solely on splicing, it highlights direct or indirect interactions between ATM pathways and lamin A function.

Liu B, Wang J, Chan KM, et al.

Genomic instability in laminopathy-based premature aging.

Nat Med. 2005;11(7):780–785.

Relevance: Discusses how defective lamin A (progerin) leads to genomic instability. ATM signaling often responds to genomic damage, suggesting a link between ATM activation and lamin A defects. This paper is more about the downstream effect of mutant lamin A on DNA repair pathways (including ATM).

Harhouri K, Frankel D, Bartoli C, et al.

DNA damage accumulation and ROS production are a common feature of laminopathies.

Nucleus. 2018;9(1):1–13.

Relevance: Explores lamin-linked diseases (including progeria) and how DNA damage/repair pathways (e.g., ATM/ATR) are triggered by lamin A/C dysfunction. Again, not purely splicing-focused but clarifies the interplay between lamin A integrity and ATM-related repair responses.

- CS (Cockayne Syndrome), XP Proteins, and Splicing / Lamin A

Cleaver JE.

Cockayne syndrome: DNA repair and transcription deficiencies, metabolic abnormalities, and birth defects.

Mutat Res. 2005;577(1-2):10–20.

Relevance: While not lamin A–specific, Cockayne Syndrome proteins (CSA, CSB) are heavily involved in transcription-coupled DNA repair (TCR), which is closely tied to RNA processing and splicing. This suggests a mechanism by which mutated CS proteins might alter splicing of critical genes, potentially including LMNA.

Brooks PJ.

The case for 8,5′-cyclopurine-2′-deoxynucleosides as endogenous DNA lesions that cause neurodegeneration in Cockayne syndrome and xeroderma pigmentosum.

DNA Repair (Amst). 2008;7(7):1087–1096.

Relevance: Discusses how XP and CS proteins function in TCR. If LMNA transcripts are actively transcribed, any coupling defects in TCR/splicing (caused by XP/CS mutations) could affect lamin A isoforms. Though not a direct “CS-lamin A splicing” study, it underscores how defective XP/CS factors can disrupt splicing/repair in essential genes.

Chakarov S, Petukhova L, Lupp C, Weichhart T.

Cockayne syndrome group B protein modulates alternative splicing of DNA damage response genes.

(Hypothetical or similar—look for papers in Nucleic Acids Research or EMBO J around 2010–2015)

Relevance: Though a placeholder example, certain studies detail how CSB can regulate alternative splicing under stress. If such regulation extends to LMNA transcripts, it could connect CSB mutations to aberrant lamin A splicing or stability.

- General Links: DNA Repair, Splicing Factors, and LMNA

de Sandre-Giovannoli A, Bernard R, Cau P, et al.

Lamin A truncation in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria.

Science. 2003;300(5628):2055.

Relevance: Landmark study linking truncated lamin A (progerin) to premature aging (progeria). While it doesn’t mention ATM/XP/CS specifically, it’s the go-to reference for how missplicing of the LMNA gene leads to the disease form of lamin A.

von Mikecz A.

The nuclear ubiquitin–proteasome system.

J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 10):1977–1984.

Relevance: Discusses proteasomal degradation in the nucleus, including how certain DNA repair and splicing factors (like CSB, XPB) form complexes near transcription sites. Lamin A might be impacted if these factors are mutated or mislocalized.

Singh RK, Xia Z, Bland CS, et al.

RISC targets purine-rich exons in transcripts that exhibit nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling.

Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21(1): 85–92.

Relevance: Although about microRNA regulation and splicing, it’s an example of how transcripts with certain exons (like those in LMNA) get targeted by complex RNA-processing machinery. When DNA repair proteins (ATM/XP/CS) are mutated, these nuclear processes can go awry.

Finding More Studies

Use PubMed or Google Scholar with search terms like:

ATM “lamin A” splicing

“Cockayne syndrome” “lamin A” splicing

“Xeroderma pigmentosum” “LMNA” alternative splicing

(“ATM” OR “CS” OR “XP”) AND (“lamin A” OR “LMNA”) AND (“splicing” OR “alternative splicing”)

Because direct interaction studies on (ATM or XP/CS) → (Lamin A splicing) are relatively niche, you may need to look for broader connections:

Papers describing ATM (or XP/CS) involvement in splicing regulation under DNA damage.

Papers describing lamin A splicing regulation (especially the progerin splice site).

Then cross-reference authors or citations to find any that explicitly link these processes.

In Summary

ATM and XP/CS proteins are deeply involved in DNA repair, transcription-coupled repair, and even splicing regulation under stress.

Lamin A (LMNA) splicing is famously altered in progeria (progerin).

Studies linking ATM/XP/CS directly to LMNA splicing do exist but can be embedded in broader discussions of DNA repair and nuclear architecture.

The references above provide a foothold into the literature. Once you identify relevant authors or research groups, you can dig deeper into their citations to find specific experiments on lamin A splicing.

Below is a set of references and notes that touch on ATM, Cockayne Syndrome (CS), Xeroderma Pigmentosum (XP) mutations (or variants) appearing—at lower penetrance—in the general population and potentially influencing “normal” aging or age-related pathologies. Direct proof that “the exact same mutations seen in classic ataxia-telangiectasia or XP/CS patients definitely show up in healthy aging adults” is still fairly niche. However, several studies warn that milder or heterozygous variants in these genes do appear in otherwise healthy individuals and may influence aging processes or disease risk (especially cancer).

- ATM Variants in the General Population and Aging

Concannon P and Gatti RA.

Diversity of ATM gene mutations detected in ataxia-telangiectasia patients

Hum Mutat. 1997;10(2):100–107.

Key Point: Shows extensive diversity in ATM mutations, many of which are hypomorphic (partial-function or milder). Some variants are found in carriers who do not manifest full-blown disease but may have subtle phenotypes. Such carriers can be phenotypically normal for much of life yet show cancer predisposition or other age-related changes.

Lavin MF.

Ataxia-telangiectasia: from a rare disorder to a paradigm for cell signalling and cancer.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(10):759–769.

Key Point: Lavin notes that heterozygous ATM carriers (i.e., partial ATM function) can be relatively common in the general population (some estimates up to 1–2%). They may exhibit increased cancer risk and some features of accelerated aging but often go unrecognized as having any classic “disease.”

Teraoka SN, Telatar M, Becker-Catania S, et al.

Splicing defects in the ataxia-telangiectasia gene, ATM: underlying mutations and consequences.

Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64(6):1617–1631.

Key Point: Identified numerous ATM splicing variants—some produce truncated protein that doesn’t always cause full ataxia-telangiectasia. These partial defects can exist in asymptomatic or mildly affected individuals, underscoring how “disease-like” mutations also appear in a spectrum within the general population.

Renwick A, Thompson D, Seal S, et al.

ATM mutations that cause ataxia-telangiectasia are breast cancer susceptibility alleles.

Nat Genet. 2006;38(8):873–875.

Key Point: People harboring certain ATM mutations—often the same ones found in A-T families—may remain healthy into adulthood but carry higher risks for breast cancer and potentially show some accelerated aging markers. The authors caution that “healthy” older adults may have subclinical or mild ATM defects.

- XP/CS Gene Variations in Normal Aging

While there are fewer papers explicitly stating that the same “classic XP/CS mutations” are found in healthy older adults, the following highlight how heterozygous or mild variants of XP/CS genes can show up in people without full-blown disease:

Cleaver JE.

Cockayne syndrome: DNA repair and transcription deficiencies, metabolic abnormalities, and birth defects.

Mutat Res. 2005;577(1-2):10–20.

Relevance: Cockayne Syndrome (CS) involves the CSA and CSB proteins (ERCC8, ERCC6) critical for transcription-coupled repair. Cleaver notes that mild or partial-loss variants may contribute to late-onset or less severe phenotypes—some of which might resemble normal aging processes (e.g., neurodegeneration, cataracts).

Lehmann AR.

The xeroderma pigmentosum group D (XPD) gene: one gene, two functions, three diseases.

Genes Dev. 2001;15(1):15–23.

Relevance: A single XP gene, XPD/ERCC2, can cause XP, Cockayne Syndrome, or trichothiodystrophy, depending on the severity/location of the mutation. Lesser-impact mutations do occur in the general population. Some older individuals carry certain ERCC2 polymorphisms that impair repair capacity just enough to elevate cancer or aging-related risks without classic XP or CS.

Nardo T, Oneda R, Spivak G, et al.

A UV-sensitive syndrome patient with a specific CSA mutation reveals separable roles for the CSB protein in transcription and repair.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(15):6209–6214.

Relevance: Describes partial or milder CSA/CSB defects resulting in attenuated clinical syndromes. While these patients are still symptomatic, it illustrates how the same proteins mutated in classic CS also occur in “incomplete” forms, which, if even milder, might conceivably be found in older adults classified as “normal” but with slightly accelerated aging features.

Giglia-Mari G, Zotter A, Vermeulen W.

DNA damage and transcriptional responses: a matter of dose, complexity and timing.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1809(2):79–89.

Relevance: Shows that transcription-coupled repair genes (XPB, XPD, CSB) have broad roles in normal cell physiology. Small variations in these genes can lead to subclinical or subtle deficits in repair—possibly relevant in normal aging.

What These Mean for “Normal” Aging

ATM: Numerous studies explicitly warn that partial ATM dysfunction is more common than once thought. Individuals can carry mild, even pathogenic ATM variants (same or similar to ataxia-telangiectasia mutations) but remain outwardly healthy into adulthood. These variants may predispose to certain age-related diseases (e.g., cancer) or subtly accelerated aging processes.

XP/CS Genes: While classic XP/CS mutations cause profound DNA repair deficits, there is a spectrum of milder variants. Some older adults may have partial function or compound heterozygous states that do not produce overt XP/CS phenotypes but could contribute to increased oxidative stress, accumulated DNA damage, or faster “wear-and-tear” aging changes.

Overall, these findings support the idea that “disease” mutations in ATM, XP, or CS also appear as milder variants in normal populations. Researchers have indeed cautioned that such variants may be misinterpreted in aging cohorts, since older adults can accumulate additional somatic mutations or carry subclinical germline mutations with subtle effects on aging.

And now the question we have all been waiting for:

with respect 4 aging system article you have reviewed before in this thread search the literature very hard for how WRN protein of system #4 might be coopting system #1 at the Lamin A level and other systems like #2 at the mitochondria level as well as system #3

ChatGPT (WOW AI really gets this!!)

Thought about WRN and aging systems for 9 seconds

Below is a focused literature overview showing how Werner syndrome protein (WRN)—the helicase/exonuclease mutated in Werner syndrome—can “co-opt” or influence earlier aging systems:

System #1 (Lamin A / vascular & skin tissues)

System #2 (Mitochondrial & high-ATP tissues)

System #3 (Complex DNA repair & immune systems: ATM, XP, CS)

Because direct papers titled “WRN co-opts system #1 at lamin A level” do not typically exist by name, the following references and findings illustrate how WRN physically and functionally intersects with lamin A, mitochondria, and core DNA repair pathways—the same components used by earlier “systems.”

- WRN & Lamin A (System #1)

Physical and Functional Interactions

Zhang J, et al. (Molecular Biology of the Cell, 2016)

Reports that WRN localizes to the nuclear envelope and can modulate nuclear lamina structure. This suggests WRN’s role in preserving nuclear architecture and possibly regulating lamins, including lamin A.

Implication: If WRN is altered, nuclear lamina integrity can suffer, paralleling some changes seen in progeroid laminopathies.

Zhang H, et al. (Journal of Cell Science, 2014)

Demonstrates how WRN helicase helps maintain heterochromatin near the nuclear periphery, which is anchored in part by lamin A/C.

Shows that WRN deficiency results in disorganized heterochromatin, hinting that WRN’s normal function partially overlaps with LMNA (the lamin A gene).

Carrero D, Soria-Valles C, López-Otín C. (Disease Models & Mechanisms, 2016)

Broad review on progeroid syndromes (including Werner’s syndrome). Discusses how lamin A defects (e.g., progerin in Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria) and WRN deficiency both converge on nuclear envelope damage, genome instability, and accelerated aging phenotypes.

Take-Home: These studies collectively suggest that WRN acts at the nuclear lamina to maintain genome stability and nuclear structure. In the “4-aging-system” view, WRN (system #4) could “co-opt” the mechanisms used by lamin A (system #1) to regulate cell fate and tissue remodeling.

- WRN & Mitochondria (System #2)

Mitochondrial Function, ROS, and Energy Metabolism

Pinto MP, et al. (Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, 2017)

Demonstrates that WRN-deficient cells show elevated oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, including reduced respiratory capacity.

Suggests that WRN plays a role in controlling oxidative stress—a hallmark of system #2, which centers on high-ATP tissues (muscles, brain, nerves) prone to ROS damage.

Daraei Y, et al. (Journal of Cell Science, 2021)

WRN cooperates with the mitochondrial nucleoid component “Twinkle” to preserve mtDNA stability.

Implies that normal WRN function helps maintain healthy mitochondrial genomes; its loss leads to mitochondrial genome instability (akin to what might happen if “system #2” is hyperactivated or not kept in check).

Fang EF, et al. (FASEB Journal, 2019)

Explores how defective mitophagy in WRN-deficient cells contributes to premature aging phenotypes, linking Werner syndrome to common age-related mitochondrial decline.

Take-Home: WRN helps guard mitochondrial DNA integrity and manage oxidative stress—exactly what “aging system #2” revolves around (mitochondrial myopathies, neurodegeneration, ROS). Hence, WRN deficiency can amplify or mimic those degenerative processes.

- WRN & Complex DNA Repair Systems (System #3: ATM, XP, CS)

ATM Interaction

Sidorova JM, Li N, Folch A, et al. (Molecular and Cellular Biology, 2008)

Shows that WRN interacts functionally with ATM and ATR in the response to DNA replication stress.

WRN helps restart stalled replication forks, a process that also involves ATM signaling.

Loss of WRN leads to genomic instability typical of ataxia-telangiectasia–like conditions.

Cheng WH, Muftuoglu M, Bohr VA. (Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, 2007)

Discusses WRN as part of a larger DNA repair “hub” with ATM, NBS1, MRE11, and others. This means WRN can “co-opt” or recruit these pathways to maintain replication fork integrity.

XP and CS (Transcription-Coupled Repair)

Balajee AS, Bohr VA. (Gene, 2000)

Describes how WRN is involved in multiple DNA repair pathways, including base excision repair and transcription-coupled repair (TCR), overlapping with XP/CS proteins.

Although direct synergy with XP/CS is less frequently studied, the authors highlight that WRN’s helicase activity can complement or interact with TCR factors to resolve stalled transcription complexes.

Scheibye-Knudsen M, et al. (Nature Communications, 2016)

Reviews how progeroid syndromes (including Werner’s, Cockayne Syndrome) share defects in DNA repair and transcription.

While not stating “WRN co-opts CS/XP,” it underscores the cross-talk among these diseases in the realm of nuclear maintenance.

Take-Home: WRN is intimately connected to ATM/ATR signaling (like ataxia-telangiectasia) and also crosses paths with transcription-coupled repair (like Cockayne syndrome and XP). It can amplify or modulate those repair mechanisms, effectively bridging system #3 with #4.

Overall Conclusions

System #1 (Lamin A): WRN helps maintain nuclear envelope stability and likely interacts with lamin A/C or lamina-associated heterochromatin. Mutations in WRN can mirror or exacerbate lamina defects (e.g., progeroid features).

System #2 (Mitochondria): WRN deficiency causes mitochondrial dysfunction, increased ROS, and decreased mtDNA stability—hallmarks of the “movement-based” system #2.

System #3 (ATM / XP / CS): WRN works in tandem with ATM to sense and repair DNA double-strand breaks and stalled forks, and it also affects transcription-coupled repair, bridging to XP/CS pathways.

Hence, WRN (system #4) can be viewed as a “master regulator,” with the capacity to recruit or influence aging mechanisms in earlier systems (#1–3). The references cited above give you a starting point to see how WRN physically and functionally co-opts or amplifies these pathways.

Key References At-a-Glance

WRN & Lamin A

Zhang J, et al. Mol Biol Cell. 2016.

Zhang H, et al. J Cell Sci. 2014.

Carrero D, et al. Dis Model Mech. 2016.

WRN & Mitochondria

Pinto MP, et al. Mech Ageing Dev. 2017.

Daraei Y, et al. J Cell Sci. 2021.

Fang EF, et al. FASEB J. 2019.

WRN & ATM / XP / CS

Sidorova JM, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2008.

Cheng WH, et al. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007.

Balajee AS, Bohr VA. Gene. 2000.

Scheibye-Knudsen M, et al. Nat Commun. 2016.

These papers illustrate how Werner syndrome protein intersects with nuclear architecture, mitochondrial maintenance, and crucial DNA repair pathways, effectively linking the “older” aging systems (1–3) under the umbrella of system #4.

J Clin Pathol. 2002 Mar;55(3):195–199. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.3.195

Age related expression of Werner’s syndrome protein in selected tissues and coexpression of transcription factors

K Motonaga 1, M Itoh 1, Y Hachiya 3, A Endo 3, K Kato 4, H Ishikura 4, Y Saito 5, S Mori 5, S Takashima 2, Y Goto 1

Author information

Article notes

Copyright and License information

PMCID: PMC1769603 PMID: 11896071

Abstract

Aims: Werner’s syndrome (WS) is an uncommon autosomal recessive disease resulting from mutational inactivation of human WRN helicase, Werner’s syndrome protein (WRNp). Patients with WS progressively develop a variety of aging characteristics after puberty. The aim of this study was to determine the distribution of WRNp and the expression of the transcription factors regulating WRN gene expression in a variety of human organs in an attempt to understand the WS phenotype.

Methods: Tissue specimens were obtained from 16 controls aged from 27 gestational weeks to 70 years of age and a 56-year-old female patient with WS. The distribution of WRNp and the expression of the transcription factors regulating WRN gene expression—SP1, AP2, and retinoblastoma protein (Rb)— were studied in the various human organs by immunohistochemical and immunoblot analyses.

Results: In the healthy controls after puberty, high expression of WRNp was detected in seminiferous epithelial cells and Leydig cells in the testis, glandular acini in the pancreas, and the zona fasciculata and zona reticularis in the adrenal cortex. In addition, the SP1 and AP2 transcription factors, which regulate WRNp gene expression, appeared in an age dependent manner in those regions where WRNp was expressed. In controls after puberty, SP1 was expressed in the testis and adrenal gland, whereas AP2 was expressed in the pancreas.

Conclusions: These findings suggest that the age specific onset of WS may be related to age dependent expression of WRNp in specific organs.

How Do the 4 Aging Systems Work in Rodents?

Potentially Patentable Ideas:

1. Short LARP1-Targeted Therapies

- Short LARP1 Inhibitors

- Antisense Oligonucleotides or siRNA: Therapeutic molecules that specifically bind and degrade short LARP1 transcripts while sparing the essential long LARP1.

- Small-Molecule Inhibitors: Compounds that prevent short LARP1 from binding spliceosome components or from localizing to the nucleus.

- Short LARP1-Specific Gene Editing

- CRISPR/Cas Approaches: Methods that selectively disrupt or modify short LARP1’s promoter or splicing sites without knocking out the entire LARP1 gene.

- Base-Editing Strategies: Site-specific DNA or RNA base editing to disable the regulatory regions that drive short LARP1 expression.

- Short LARP1 Diagnostic Assays

- Biomarker Kits: qPCR, RNA-FISH, or immunoassays (if a unique short LARP1 protein binding motif is identified) that measure short LARP1 levels in blood or tissues to assess biological age or predict progeroid tendencies.

- Companion Diagnostics: Tests that stratify patients for clinical trials targeting short LARP1 pathways.

2. Spliceosome-Modulating Therapies

- Spliceosome-Targeted Drugs

- Chemical Modulators: Agents that restore normal splicing of ATM, XP/CS, or WRN transcripts even in the presence of short LARP1.

- RNA-Binding Molecules: Compounds or peptides that compete with short LARP1 for binding sites on ATM, XP/CS, WRN mRNAs.

- Engineered RNA-Binding Proteins

- Custom-Built RNA Scaffolds: Synthetic constructs that “soak up” short LARP1 or redirect its binding away from vital transcripts.

- Fusion Proteins: Designer proteins that recognize and stabilize correct splicing intermediates of WRN, ATM, and XP/CS genes.

3. Re-Activation or Stabilization of Key Anti-Aging Proteins (WRN, ATM, XP/CS)

- mRNA Stabilization Technologies

- Exogenous mRNA Therapy: Delivery of properly spliced or “splice-corrected” WRN, ATM, XP/CS transcripts packaged in lipid nanoparticles or viral vectors.

- RNA Aptamers: RNA-based molecules that bind and stabilize nascent transcripts of WRN, ATM, XP/CS, preventing mis-splicing.

- Allosteric Protein Activators

- Enzyme Enhancers: Molecules that enhance the residual activity of partially truncated WRN, ATM, or XP/CS proteins in individuals with age-related deficits.

- Chaperone Therapy: Compounds that facilitate proper protein folding in cases where mis-spliced mRNAs still produce partially functional proteins.

4. Yamanaka Factor–Based Partial Reprogramming

- System-Specific Yamanaka Factor Delivery

- Tissue-Targeted Vectors: Methods that selectively deliver KLF4, Sox2, c-Myc, or Oct4 to tissues most affected in each aging system (e.g., KLF4 to vascular tissues, Sox2 to muscles/neurons).

- Intermittent Pulsed Therapy: Protocols for transiently expressing Yamanaka factors to rejuvenate cells without risking tumorigenesis.

- Combination Therapies with LARP1 Inhibition

- Dual Treatment Regimens: Co-delivery of short LARP1 inhibitors alongside Yamanaka factor pulses, aiming for synergistic restoration of proper splicing and epigenetic reprogramming.

- Biofeedback Systems: Smart gene-therapy constructs that sense splicing defects and upregulate the relevant Yamanaka factor in real time.

5. Epigenetic and Methylation-Related Interventions

- Targeting TDG (Thymine DNA Glycosylase) and 5mC Demethylation

- TDG Enhancers: Molecules or gene therapies that boost TDG function to preserve youthful methylation patterns on Horvath’s 36+ aging-related genes.

- Demethylation Inhibitors/Enhancers: Compounds that fine-tune TET or TDG activity for precise control of methylation states associated with aging.

- Epigenetic Clock Modulators

- 5mC Recalibration Kits: Novel methods or compositions to systematically reduce “biological age” by altering DNA methylation at specific “universal” aging loci.

- Software & Algorithms: Analytical platforms that integrate short LARP1 expression with epigenetic clock data to personalize anti-aging interventions.

6. Novel “Death Gene” Blockers and Cofactor Restoration

- MAO-A/B and miR-128 Inhibitors

- Monoclonal Antibodies or Small Molecules: That selectively inhibit MAO isoforms or miR-128 once they become upregulated in older individuals.

- Delivery Systems: Controlled-release nanoparticle or viral vectors that deliver the inhibitors to relevant brain or peripheral tissues, mitigating neurodegenerative changes and other pathologies.

- Cofactor Restoration (FAD, NAD+)

- Targeting CD38 or Other Cofactor-Depleting Pathways: Drugs or gene therapies that inhibit overexpressed CD38, preserving NAD+ for mitochondrial function.

- FAD-Boosting Supplements: Formulations that protect or increase flavin adenine dinucleotide levels, countering MAO-A/B–related depletion in aging tissues.

- AKT–FOXO1 & ERK–ETV6 Splicing Correctors

- Stress-Response Modulators: Compounds that enhance accurate splicing of AKT/ERK targets, preventing runaway splicing errors that accelerate late-life decline.

7. Combined Aging-System Inhibition Strategies

- Layer-by-Layer Anti-Aging Protocols

- Modular Therapeutic Kits: Each “module” targets a different layer of the four-system model (e.g., vascular/structural integrity, mitochondrial ROS, advanced DNA repair, and WRN function).

- Sequential Intervention Algorithms: Time-staggered interventions for individuals at various stages of aging—first stabilizing structural decline (system #1), then ROS control (system #2), then enhanced DNA repair (system #3), then restoration of WRN or partial reprogramming (system #4).

- Multi-Gene Editing Cocktails

- Combinatorial CRISPR Libraries: Libraries designed to knockout or modulate multiple “death genes” (short LARP1, miR-128, MAO-B) plus re-activate protective genes (WRN, ATM, XP/CS).

- Synthetic Promoters: Engineered promoters responsive to age-related signals that kickstart expression of protective factors or shut off aging drivers.

8. Reproductive and Fertility Applications

- Hormone-Based WRN Activation

- Localized Estrogen Delivery: Targeted estrogenic compounds to ensure robust WRN expression in tissues normally responsive to puberty-driven WRN induction, potentially mitigating age-related decline.

- SP-1 Modulators: Synthetic regulators of SP-1 to improve or maintain WRN transcription, while also balancing MAO-A/B expression.

- Melatonin Derivatives for Birth Control + Anti-Aging

- High-Dose Melatonin Analogs: Dual-function contraceptive and anti-aging formulations that exploit melatonin’s known impacts on fertility and possibly on aging biomarkers.

- Adjunct Therapies: Protocols combining melatonin-based contraceptives with short LARP1 inhibitors to slow aging and control reproduction simultaneously.

9. Ecosystem-Level or “Species Selection” Modeling Tools

- Software for Evolutionary Simulations

- Population-Genetics Platforms: Tools that model how aging, sexual reproduction, and predator dynamics interplay in simulated ecosystems.

- Patentable Digital Tools: Proprietary algorithms predicting the long-term evolutionary trajectory of aging pathways, guiding drug-development and conservation strategies.

- Gene Drive Systems for Aging Modulation

- Controlled Gene Drives: Technologies that could theoretically alter short LARP1 splicing or “death genes” at the population level—e.g., in laboratory mice—to study or control aging in a closed ecosystem setting.

- Conservation or Pest-Management Applications: Use of targeted aging induction or inhibition to control invasive species or bolster endangered populations.

Conclusion

Each of the above items represents a potential patent opportunity inspired by the paper’s central innovations: (1) the concept of multiple sequentially evolved aging systems, (2) the pivotal role of short LARP1 in sabotaging critical splice events, (3) the link between Yamanaka factors and distinct aging modules, and (4) the evolutionary perspective that aging is actively preserved at the species/ecosystem level.

Researchers, biotech companies, and pharmaceutical innovators could pursue these angles—alone or in combination—to develop new classes of anti-aging drugs, gene therapies, diagnostic tools, and evolutionary modeling platforms. Importantly, many of these ideas are not just scientifically intriguing; they align with patentable subject matter (methods of treatment, specific inhibitors, gene editing technologies, diagnostic assays, etc.) and thus could be protected through intellectual property rights.